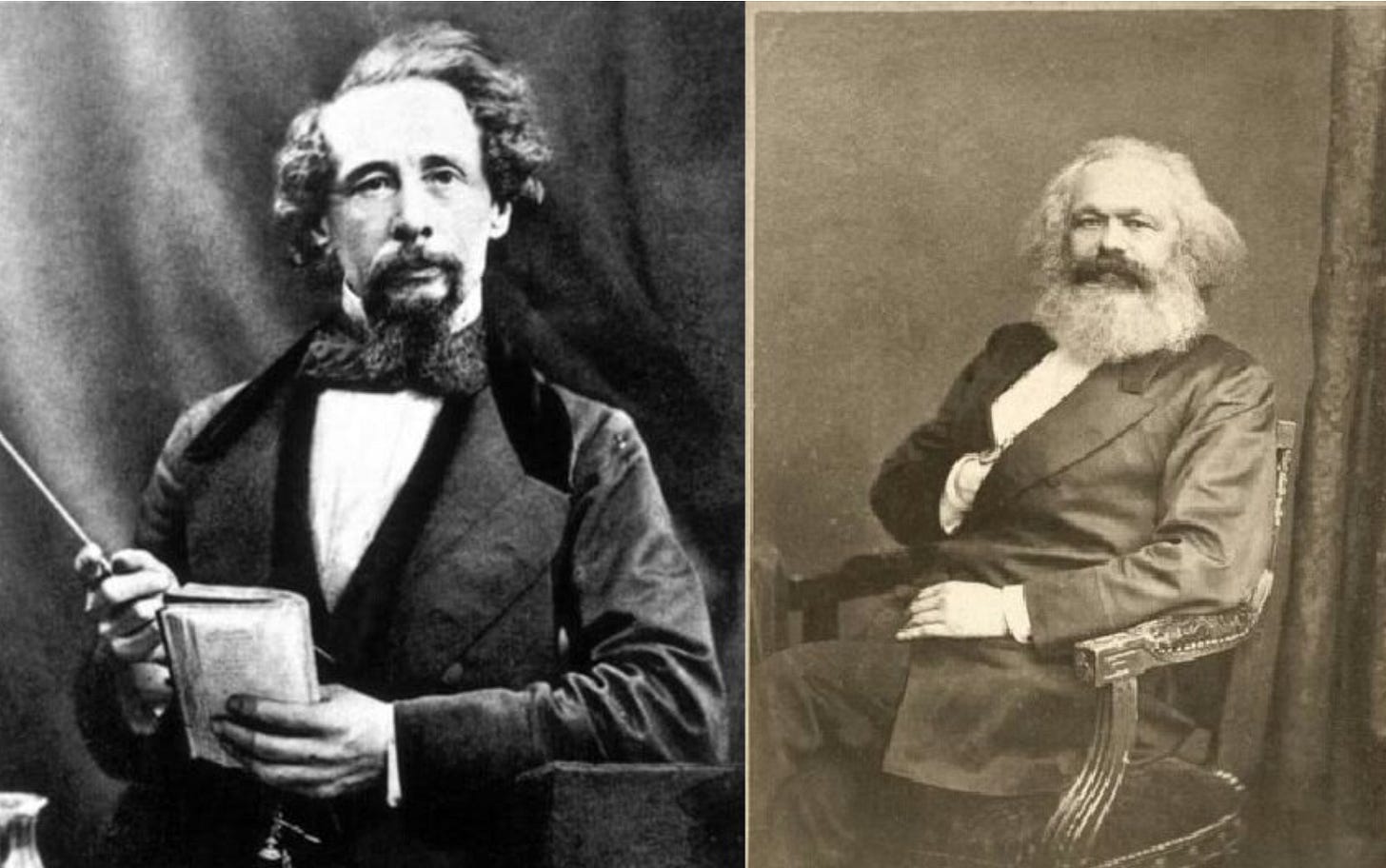

The Politics of Scrooge: Charles Dickens and Karl Marx Saw the Same Industrial Revolution, But Came to Very Different Conclusions

Dickens created A Christmas Carol. Marx created Das Kapital. Their only point of agreement: Healthcare shouldn’t be tied to your employer.

Dickens Thought Bosses Should Be Shamed Into Better Wages, Where Marx Thought Workers Should Seize the Means of Production.

More than any pundit or political scientist, Charles Dickens provides the clearest frame for understanding modern politics. How you assess Ebenezer Scrooge is a good shorthand for one’s politics because Charles Dickens’s assessment of poverty is, in a profound way, the foundation for both sides of modern European-American politics.

Up front, it should be said that Charles Dickens, like Jacob Marley is dead: to begin with. There is no doubt whatever, about that. Old Dickens is as dead as door-nail.

And yet, Dickens really isn’t dead at all. Look at the community theater marquee in any English-speaking town after the American Thanksgiving holiday: There’s no entertainer more alive than Charles Dickens, except for another pop icon who resurrected her career with a Christmas hit after near career-ending bombs.

Christmas Hits Are Gifts That Keep On Giving (Until The Copyright Runs Out and They Enter the Public Domain!)

It’s more exact to say that the undead specter of Charles Dickens still haunts the politics of capitalism, like the three ghosts (plus Jacob Marley, who is visiting from an unnamed purgatory).

This exchange from one of the most polarized and consequential Prime Ministerial elections in British history, the 2019 contest between Tory leader Boris Johnson and Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, illustrates the point. Like many things in British English, it doesn’t quite translate to call Johnson “Brit-Trump” and Corbyn “The British Bernie,” but you’ll grasp the basic American Conservative / Liberal worldview.

Towards the end of the debate, the moderator asks the candidates what they would gift each other for Christmas, and Corbyn says that Mr. Johnson–who, like a true man of the people, would show off his Classics-based education from Eton and Oxford by reading from The Iliad in its original Greek–”likes a good read.”

“So what I would probably leave under the tree for him is A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, and then he can understand how nasty Scrooge was.

It’s a great political zinger because it taps into something intuitively true: There’s no better way to explain nine years of crippling Tory austerity than by comparing it to the miserly Scrooge. It’s such a good line that Boris gives it a hearty laugh, and can only come back with gifting Corbyn “a copy of my brilliant Brexit deal.” Which, to be fair, is its own reflection of reactionary politics that struck something deep within the English psyche in its time and place.

The zinger also helps us understand the Right / Left divide in political thinking in modern Anglo-American societies: Why are the poor…poor?

Is Jeremy Corbyn right, that poverty is systematic, the result of a system designed to trap the working class in poverty so their continued exploitation will produce wealth for the capital-owning class? Or is Boris Johnson right, that the poor are lazy no-goods who would be less poor if they just got a job, pulled themselves up by their bootstraps, and showed their value in the capitalist marketplace?

This is why Scrooge endures. On the left hand, A Christmas Carol affirms the belief that the system is designed to exploit workers like Bob Cratchit, who shows up and works hard and loves his family, but is still at the mercy of capitalist goons like his boss, who lacks the basic humanity to pay him enough to let them live a decent life.

On the right hand, A Christmas Carol affirms the belief that if I’m an individually good and charitable person, then I am not morally culpable for the system’s evils because I am doing my part as a job-creator, and as an individual during the Christmas season, I do the right thing by giving of my largesse. Maybe there’s something wrong with the system, but everybody has the opportunity to succeed, and besides, my heart is in the right place, and that’s what matters.

So, if you don’t think about A Christmas Carol too deeply, it speaks to everyone, no matter where they sit on the political spectrum. This is why it’s evolved into an agreeably comfortable, civic-spiritual ritual.

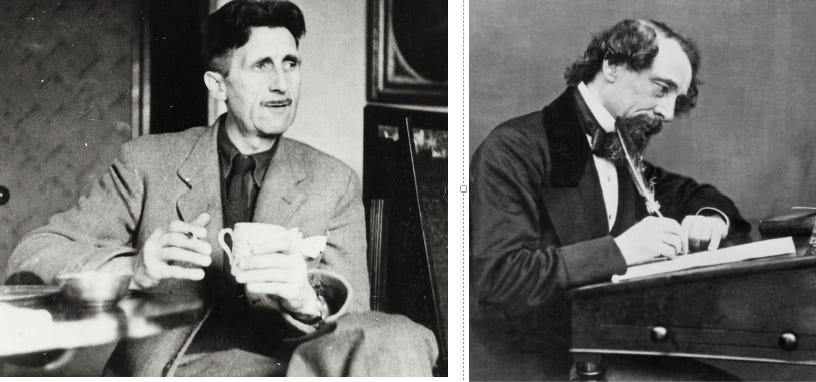

But I would argue that A Christmas Carol is a work of Great Literature with a capital L, in ways that only reveal themselves upon close reading. Charles Dickens was absolutely not a Leftist, nor was he a Tory. Both sides try to claim him, but Dickens defies political classification because he’s an enigma: As Orwell observed, no writer has ever attacked his own country’s institutions with such ferocity and become such an institution himself. His worldview is the foundation of Anglo-American politics. There’s no politician, political scientist, pundit, anybody who has better described modern politics than Charles Dickens.

Let’s understand why. Our guide for this journey, like a Ghost of Christmas Past of English writers whose name we still recognize today, is George Orwell. In 1939, on the brink of World War II and after having fought in the Spanish Civil War (and having a near-death experience with Trotskyites, then settling down to a life in England with a rooster named Henry Ford and a poodle named Marx), George Orwell wrote a long essay about the most famous English novelist.

So let’s step through Orwell’s essay to help us understand why Dickens pretty much explains politics, and how all this is inextricable from Marx and the origins of Communist theory.

Dudes Rock, English Literary Icons Edition

Unless you thought I was overreading Dickens’ relationship to class consciousness and Marxism, Orwell opens his Dickens essay with an anecdote about Nadezhda Krupskaya, the wife and revolutionary partner of Vladimir Lenin, saying that he walked out of Dickens’ The Cricket on the Hearth because of its “(intolerable) middle-class sentimentality.” Fair enough, and this is indeed the most potent and lasting criticism of Dickens. Not only did the Bolsheviks believe it, but Oscar Wilde said about The Olde Curiosity Shop, “One must have a heart of stone to read the death of Little Nell without laughing.”

So, no, Dickens was not a “proletarian” writer. He was a social justice advocate who used his considerable stature to campaign against obviously barbaric practices like the death penalty. But as Orwell says, Dickens never really wrote about the working class, and when he did, they were often pitiful objects or comic relief Cockney buffoons, the Victorian novelist’s version of Dick Van Dyke in Mary Poppins. Or, they were criminals, like the gang in Oliver Twist who would have felt at home in The Wire.

Rather, Dickens’ stories are middle-class: As Orwell says, Dickens’ “real subject-matter is the London commercial bourgeoisie and their hangers-on–lawyers, clerks, tradesmen, innkeepers, small craftsman, and services. There are very few agricultural or industrial workers to be found.”

So, Dickens was not a socialist, or in Orwell’s words, “the kind of well-meaning idiot who thinks that the world will be perfect if you amend a few bylaws and abolish a few anomalies.” Dickens pitied the working class, and he well understood how the existing order exploited them. As Orwell says, Dickens “attacks the law, parliamentary government, the education system, and so forth, without ever clearly suggesting what he would put in their places.” He never really suggests that the system should be overthrown, or suggests that “the economic system is wrong as a system.”

You can see this in A Christmas Carol: He wrote this book in 1843, and nowhere in this story does Dickens suggest any of the political reforms championed by the liberal bourgeoisie in the revolutions of 1848, which were already being advocated in the literature of the time. Dickens also never hints at any of the working class reforms demanded by the artisans and factory men on the barricades in 1848, who were the grandchildren of the sans-culottes working men of the French Revolution, and the forefathers of socialist and communist revolutions to come.

Really, even though Scrooge has an individual epiphany that he should treat his employee better, Dickens never suggests that the system itself is the problem. In fact, the story ends with everybody in their proper place, but Bob Cratchit got enough of a raise to cover his son’s healthcare, and the family got a goose from the boss. That’s pretty much it.

Orwell is right: No wonder Vladimir Lenin was disgusted by Charles Dickens.

Unknown Photographer Of Lenin and Krupskaya Leaving “The Cricket on the Hearth.” (1922). No Stars for Dickens, Did Not Like, Too Bourgeois, Not Enough Class Conflict

Here’s where I’d like to leave Orwell for a moment to explain what, for me, is one of the most fascinating things in modern history:

In October 1843, both Charles Dickens and Friedrich Engels were in Manchester, England, witnessing the worst horrors of the Industrial Revolution.

One wrote A Christmas Carol. The other wrote Outlines of a Critique of Political Economy, which Karl Marx would later use as the basis for Das Kapital.

This is where A Christmas Carol becomes more than a parable about why your family’s health care shouldn’t be tied to your employer, and why it’s a great work of Literature with a Capital L: