The “Noisiest Authorities”: Charles Dickens Explains How It Can Be Both the Best and Worst of Times in the Age of Trump

The World’s First Global Media Star Understood the Power of Attention

These Guys Both Understood That Attention Is More Powerful Than Money

Days before the Second Inauguration of Donald Trump, I listened to this podcast episode, a conversation between Ezra Klein and Chris Hayes on Hayes’ new book, The Sirens’ Call. I haven’t read the book, but based on this conversation, this is how I understand the thesis:

In the post-industrial modern world, our most important and scarcest commodity is attention.

In Hayes’ framing, our political system is best understood as “Attention Capitalism.” Meaning, as modern technology has increased our ability to produce “content,” power is increasingly concentrated in those who command attention on their content. Money is important because it buys the means to produce, distribute, and control content, but money itself is really just a means to the attention that influences minds and directs actions.

Whatever you think of Hayes and Klein, it’s not a coincidence that two guys who rose up out of the Blog Era of the early internet to become international media stars hit upon this thesis. For me, Hayes and Klein are two of the most thoughtful left-of-center pundits, diving deeper into philosophy and history in their longform podcasts and books. Here, Hayes traces “Attention Capitalism” to the Industrial Revolution, in which:

“human effort gets embedded in a set of in a set of institutions–legal institutions, market institutions–that commodify it so that every hour of wage labor is equal to every other hour of wage labor and then sold on a market for a price.”

That is what tech companies do with attention: Literally, our attention–through clicks, time spent on sites, other measurables–is commodified, priced, and sold. Now, this is how our politics is conducted.

For me, this is the story of the 2024 Election: If you watched the campaigns through traditional outlets–the conventions, the debates, the rallies, the mainstream media–the Democrats were winning. But, what the Trump Campaign understood better, which made the vital difference, is that the real attention of low-information, low-engagement voters isn’t held in these spaces: There’s a whole media ecosystem driven by social media content, podcasters, etc. that wield real influence.

It Was Cool, But The Voters Harris Needed Weren’t Watching

The task of understanding how to deal with the daily onslaught of Trump is understanding how to manage your own attention. Focusing on the day-to-day details of this controversy or that outrage actually obscures things. In fact, that’s what the authoritarian thrives on: By extracting your attention, you become distracted and exhausted so that eventually, as Winston Smith says in the last line of 1984, “He won victory over himself…He loved Big Brother.”

He Won the Victory Over Himself By Giving Big Brother All His Attention. “Nineteen Eighty-Four” by Michael Radford (1984).

This is where the first paragraph of A Tale of Two Cities (read it here) really is prescient, anticipating the melding of politics and media in the post-Industrial Age, written by the man best positioned to understand it. “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times” isn’t Dickens’ thesis: He synthesizes the paradox after a dash that directs you to his point:

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness, it was the epoch of belief, it was the epoch of incredulity, it was the season of Light, it was the season of Darkness, it was the spring of hope, it was the winter of despair, we had everything before us, we had nothing before us, we were all going direct to Heaven, we were all going direct the other way–in short, the period was so far like the present period, that some of its noisiest authorities insisted on its being received, for good or for evil, in the superlative degree of comparison only.

Now you see it. It’s the best and worst of times at the same time depending on who you’re giving your attention to. On Chris Hayes’ MSNBC or Ezra Klein's podcast, it really is the worst of times: Democracy is falling apart, the Trump Dictatorship will evolve into some form of the Third Reich and Putin’s Oligarchy. On Fox News, and more importantly, the entire underground right-wing media ecosystem, it’s the best of times because President Trump is here to restore order after the worst of times under Joe Biden.

In other words, the “noisiest authorities” tell us how to feel through media ecosystems that create the vibes which infect our thoughts and influence our political actions. The joy and the outrage: Everything has to be good or evil in the superlative all the time to keep our attention.

Charles Dickens was, first and foremost, a media man. He began professional life as a Parliamentary reporter, and never stopped doing journalism throughout his prolific career as a novelist. In 1836 at 24 years old, he first gained fame with Sketches by Boz, a series of short biographical sketches of real people that read with Dickens’ characteristic detailed, witty prose. This merging of “sketched” non-fiction into fiction led to The Pickwick Papers, which catapulted Dickens into international stardom. Dickens’ timing couldn’t have been better: Lord Stanhope’s cast iron printing press produced more books, with more advertising, shipped widely on new railways.

Long story short, Dickens created himself as the world’s first “authorpreneur,” Using the “sketches” format, Dickens negotiated an arrangement that made serialized storytelling a viable business. In his deal with Chapman and Hall, Dickens “revolutionized nineteenth-century publishing, distribution, bookselling, author-publisher relations, copyright provisions, and of course fiction itself.”

Dickens’ weekly sketches commanded attention across the world, but because his publisher Chapman and Hall owned Pickwick’s copyright, Dickens didn’t reap the rewards. Charles Dickens never let it go, beginning Charles Dickens’ lifelong feud with publishers who didn’t seem to understand that they were profiting off the audience’s attention on Charles Dickens, which should be owned and monetized by Charles Dickens.

Dickens continued to publish serially, his fiction headlining weekly magazines that were, content-wise, mostly non-fiction journalism focused on social justice issues. Dickens’ fiction was headlining these subscriptions, so in the 1850s, he negotiated a deal to own 50% of Household Words, a weekly publication of un-bylined journalism that became a vehicle for Dickens’ serialized novels. He also assured that Household Words was “Conducted By Charles Dickens.”

Dickens, more than his publishers, grasped how technological advancements created more avenues for attention. Dickens wrote for a mass audience, and encouraged his publishers to distribute his work through media designed to reach different segments of that audience. He sold cheap pamphlets of his work, laden with advertisements that targeted the working class. He sold subscriptions to Household Words that targeted the middle class. With A Christmas Carol, he sold gold-flecked heirloom books. He started touring, earning a substantial income from live performances. He created his own small theater company (starring him in the lead, where he met his mistress).

The Author’s Picture of Original A Tale of Two Cities Pamphlets, Held at the National Art Library in the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Forster Collection of Dickens’ Personal Artifacts.

To be clear, Dickens was terrible with money, overspending and overextending almost his entire life. But, better understood, Dickens spent money to gain attention, creating a public life in which he played the role of “Charles Dickens.” He understood himself as a brand, which he married to his writing style: Dickens wrote in “First Person Omniscient,” using “I” to tell a story as if he, Charles Dickens, is right there in your sitting room telling you a story. All the pieces in Household Words are “conducted” by Charles Dickens. Even his amateur theater troupe was “Under the Management of Mr. Charles Dickens.” In this way, Dickens created himself as an individual brand, designed to transcend his publishers in the same way that, say, Miley Cyrus transcended Disney and Hannah Montana.

The Tavistock House Theater Was Actually Dickens’ House Off Tavistock Square.

This active curation of Brand Dickens was the performance of Dickens’ life So, when the publishers Bradbury and Evans refused to print Dickens’ “personal statement” about his very shady divorce, he quit Household Words to self-publish and (mostly) self-own a new journal: All The Year Round.

Dickens bet on himself, believing that he, as a personal brand, was bigger than the legacy platforms most artists relied on. ATYR was, like Household Words, a middle-class publication mostly filled with social-justice journalism. Dickens launched ATYR with the first serial of A Tale of Two Cities right there on the cover, and it was the best of times for Dickens, with subscriptions so successful that he immediately paid off all the production costs and turned a profit of, in today’s dollars, about $100,000. Dickens was so petty that he sued Bradbury and Evans for the name Household Words, won the suit, and then titled it All the Year Round. A Weekly Journal. Conducted by Charles Dickens. With Which Is Incorporated Household Words.”

He Bet On Himself And Won Bigger Than Any Author In History: Dickens Launched His Self-Published Journal With What Became the Best Selling English Language Novel of All Time.

This is Dickens’ personal context when he wrote the first paragraph of A Tale of Two Cities. All his attention had been directed at his own attention. By this time, he was something like a proto media-mogul. He’d become a worldwide celebrity, toured the United States, invented modern Christmas, lobbied for successful Parliamentary legislation, founded philanthropies–most of his waking moments were spent getting and directing attention. Dickens also understood that his fame would outlast his life, that attention would be paid to it, so he fed his abandoned autobiography to his best friend and hand-picked biographer to curate his legacy after he died.

More than any other public figure, Charles Dickens understood that cultural and political influence ran partly through money, but mostly by being one of the “noisiest authorities” ginning up the day’s events in the superlative degree. Everything is evidence that society is wise/foolish, believable/incredulous, Light/Dark, hope/despair, everything/nothing, that we’re all going direct to Heaven or direct the other way. That’s how a media man moves copy! Nobody moved more copy than Charles Dickens!

A true testament to Dickens’ insight is that he recognized that what was happening to him wasn’t, in itself, new. Technology made it seem new, but really, he was experiencing newly amplified human nature. The methods and scale are new, but society has always been like this. The authorities are just a little bit noisier.

In the Enlightenment France that laid the intellectual groundwork for the Revolution, the noisiest authorities were Voltaire and Rousseau. They debated the nature of the Social Contract so vigorously that today, they’re buried opposite each other in the basement of Pantheon like they’re going to yell at each other forever. In the Victorian England that laid the groundwork for our modern Anglo-American political traditions, it was the formation of the debate between the political right and political left fought by Edmund Burke and Thomas Paine.

So, dear reader, if you think you live in extraordinary times, perhaps you do, but we’ve been here before. If you believe that political polarization is the product of the pernicious rewiring of our brains by social media, I think Dickens would say that technology only amplifies human nature, just as it amplified his celebrity in the Industrial Revolution. We’ve always been this way: The Times were like this in 1789, here in 1859, and whenever you’re reading my words in the future.

Deeper than that, Dickens also understood that his brand of journalism–substantive, social justice based–was competing for attention with tabloid journalism. Voltaire and Rousseau may be famous today because they were important thinkers who influenced the Revolution, but what actually consumed people’s attention in the Age of Enlightenment? What did your average Londoner consume other than the great debate between Burke and Paine?

Dickens has an answer for that in the third paragraph of Cities, which is key to his thesis. Nobody understood how tabloid journalism moved copy more than the most famous celebrity in England, much of it about him. So, he details a couple obscure allusions that would have been familiar to his readers, which illustrates his point.

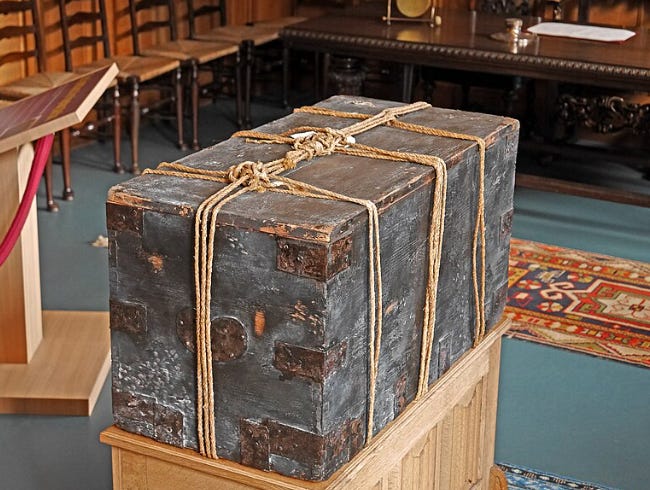

Dickens references Wesleyan “prophetess” Joanna Southcott. Dickens mashes up some dates with some other obscure references to get to 1775, but here’s what his readers would have recognized: Joanna Southcott was an unknown servant who declared herself a Woman of the Apocalypse, came to London to sell “Seals of the Lord” to the “Elect” destined for heaven, and in 1814, as age 64, declared herself pregnant with the Messiah. She did, in fact, have some abdominal swelling, but it was a serious medical condition that led to her death. This gave rise to the Southcottians, a not-insignificant sect who believe that “Joanna Southcott’s Box” contains prophecies that will save England.

This is, of course, very stupid tabloid stuff, and true to form, Dickens chose a story that lasted well beyond his years: Through the 1970s, the Panacea Society lobbied for the requisite “24 Bishops of the Church of England” to open the box. In the Year of Our Lord 2024, the “prophet’s cradle” made news on the BBC.

The Lord Requires 24 Bishops To Open This Thing

More ridiculous is Dickens’ second allusion, the Cock Lane Ghost. The details aren’t important (I will post my personal videos from Cock Lane itself, telling you all about “Scratchy Fanny’s Ghost”), but here’s the high-level: William Kent’s wife died in childbirth, he lived in sin with her sister Fanny, she died of smallpox, the landlord Richard Parsons sued on the broken lease, Parsons lost, but then claimed that Fanny’s ghost haunted Cock Lane, and he started charging admission to see the house, developing a small cottage industry of freak-show curiosity in a narrow backstreet near Smithfield Market.

Again, this is all very stupid, but it led to over a decade’s worth of high profile lawsuits, public séances(!), Parliamentary investigations, including an on-site inspection by the famous politician Horace Walpole, and a personal documentation of a séance by Samuel Johnson.

The Author’s Picture of the Entrance to Cock Lane Before Investigating This Whole Scratching Fanny Thing For Himself

After announcing Southcott and Cock Lane’s importance in the 1775 public’s attention, Dickens tells us:

“Mere messages in the earthly order of events had lately come to the English Crown and People, from a congress of British subjects in America: which, strange to relate, have proved more important to the human race than any communications yet received through any of the chickens of the Cock-lane brood.”

Dickens’ point: To move copy, the media gins up stupid tabloid non-stories, which distract our attention from actual stories, like the Declaration of Independence.

Both Dickens’ obscure allusions, which would have been familiar to his readers, have a common thread: Though obviously untrue and unimportant, the media amplification turned them into actual things that had to be dealt with by actual public officials. They took up important people’s attention!

Joanna Southcott attracted huge crowds across England, which had to be addressed by Church of England officials. Petitions to open her box took up time and energy during the Crimean War and World War I. The Cock Lane Ghost had to be dealt with by actual political luminaries of the time. England’s “most accomplished man of letters” Dr. Samuel Johnson, the literal guy who invented the literal dictionary, had to conduct an “investigative séance” of this nonsense, only to find out that the landlord’s daughter was hiding a piece of wood that made the “Scratching Fanny” noise.

This is how the paranoid style of tabloid journalism transmogrifies into conspiracy theory, which ends up doing actual damage in real life. The attention makes it real, and it has to be dealt with while the “mere messages” from colonial subjects are cared about only by “elites” who are trying to tell you what’s important. As somebody who spent two minutes reading about Melania’s meme coin yesterday, I can personally attest that Trump 2 is going to be the Cock Lane Ghost every day for the next four years.

So, if you think you live in the worst of times, that everything is dumb and driven by conspiratorial nonsense that’s distracting people from what’s really important: Well, Charles Dickens is here to tell you that it’s always been like this. He’s an Attention Merchant Of The Highest Order and knows how that game is played.

An Original Illustration of the Falling of the Bastille in A Tale of Two Cities by Hablot Browne (1859).

But A Tale of Two Cities isn’t some sensationalized, exploitative version of the French Revolution designed to sell copies to the lowest common denominator. He’s here to draw your attention to important things, and for me, it provides a clear moral path for understanding revolutionary moments like ours.

Among literary people, Cities is low on the Dickens Power Rankings. Jeff Daniels in “The Squid and the Whale” calls it “minor Dickens,” but I think that undersells it. This is Dickens’ novel that speaks through time, and it’s the one that speaks most to this moment. We live in revolutionary times, and this book helps us process the what, how, and why of social upheaval. That’s what we’ll explore in our reading of the book.

If you’re looking to train your attention on something other than the second Trump Presidency, reading A Tale of Two Cities is a great way of understanding what we’re going through without getting ground down in the everyday. What they want is your attention, and looking to the wisdom of people who’ve been here before is a way of engaging the moment without letting it exhaust your most precious commodity, your attention.

So, welcome to this journey through time. I’ll see you back here next week, when we pick up in 1775 on the Dover Road to France, recalling a dead man to life.