Part I: The French Revolution Historiography is a Series of Playbooks Written By People Who Literally Made History

All Politics From Napoleon to Trump Is Fallout From the Storming of the Bastille

Part I: Historiography and the French Revolution’s Primary Sources

The Author From Deep Within the Stacks London Library, Founded in 1841 by Thomas Carlyle, Author of The French Revolution: A History and Charles Dickens’ Primary Source for A Tale of Two Cities.

Why A Tale of Two Cities? Dickens’ Source Material Is the Intellectual Foundation for MAGA. But Dickens Also Prescribes the Antidote

A Tale of Two Cities is the Great Novel for our times, not just because all politics in the modern world is fallout from the collapse of feudalism, symbolized by the Fall of the Bastille.

It’s because there is a very clear, self-acknowledged lineage from the “House Philosopher” of today’s Techno-Fascism of the MAGA Movement, Curtis Yarvin, to his intellectual idol Thomas Carlyle, the most influential British philosopher of the 19th Century.

Carlyle’s reaction to the social upheavals that spawned Liberal Democracy and Socialism was the Great Man Theory, in which the true heroes are the singularly powerful men who use overwhelming violence to Restore Order. This was quite literally the philosophical underpinning of Nazi politics. In Hitler’s final hours in the Fuhrerbunker, he took comfort in reading Carlyle’s biography of Frederick the Great.

Carlyle’s status as the intellectual godfather of the Nazis is the thread Yarvin uses to connect the French Revolution to Fascism to MAGA. Yarvin has written that Hitler was a “genius” (but, to be fair, endorses Hitler’s ideas but not necessarily his methods and asthetics), then brings that past into the present. Yarvin’s recently connected his belief that “Hitler Spoke The Truth to Germans” to self-proclaimed Hitler admirer, Holocaust denier, and Donald Trump dinner guest Nick Fuentes’ call to ethnically cleanse Minnesota of its Somali population.

So, yes, if you want to understand how MAGA thinks, you have to understand Curtis Yarvin, who “has shaped J.D. Vance’s thinking more” than anyone. And to understand Yarvin, in Yarvin’s own words, then you need to understand Thomas Carlyle’s study of the French Revolution. Much of Yarvin’s thinking evolves from his analysis of the French Revolution, which in Yarvin’s mind resulted from Enlightenment French intellectuals getting brain poisoned by the American and English revolutionaries’ revolt against their rightful kings. This is why Thomas Carlyle is the intellectual root of Yarvin’s techno-Fascist, neo-Monarchism.

Thomas Carlyle was also Charles Dickens’ major literary and intellectual influence, and his The French Revolution: A History is Dickens’ is chief source material for A Tale of Two Cities.

But Dickens’ book isn’t just Carlyle’s philosophy in a historical fiction. Rather, the brilliance of Cities is that Dickens begins with Carlyle’s narrative and fashions something entirely his own, and in many ways, deeply contradictory to the thinking of Carlyle: A deep meditation on what it means to be a Christian in a time of state terror.

All these ideas are why A Tale of Two Cities is the Great Novel to read during Trump’s America: It helps us understand how we got here, what’s happening now, and what we can do about it.

We will get to all that. For now, let’s start at the beginning.

What Is History, Exactly?

Historiography is the study of how we come to understand history. Said another way: It’s the study of the methodology that creates both the historical record and our analysis of that record.

Or, the history of history.

Historiography isn’t merely an academic exercise. History is the stories that shape society, in large part to justify The Way Things Ought To Be. These stories are foundational not just for abstract political ideas, but in the concrete ways the law is written and executed, how policymakers decide who-gets-what, and how people relate to one another.

This is why historiography matters: Who controls the history is, mostly, who controls the material conditions of the present and the future.

For our present moment, the historiography of the French Revolution is the most important historiography to understand–even for Americans, more important than the civic mythologies of the Founding Fathers, the Civil War and World War II.

So, why choose the French Revolution as Year One?

Because this is when Enlightenment ideas were put into practice, tearing down the feudal system and ushering in the modern world’s three major political movements: Liberal Democracy, Socialism and Communism, and Fascism.

The arc of the modern world begins with the Storming of the Bastille, which eventually gave rise to Napoleon, who emerged from the rubble of the Revolution as the world’s first nationalist dictator. Napoleon’s mission was to Make France Great Again, creating a model for “enlightened despots” whose fear campaigns are drawn from tropes lifted directly from the streets of Paris during the Revolution.

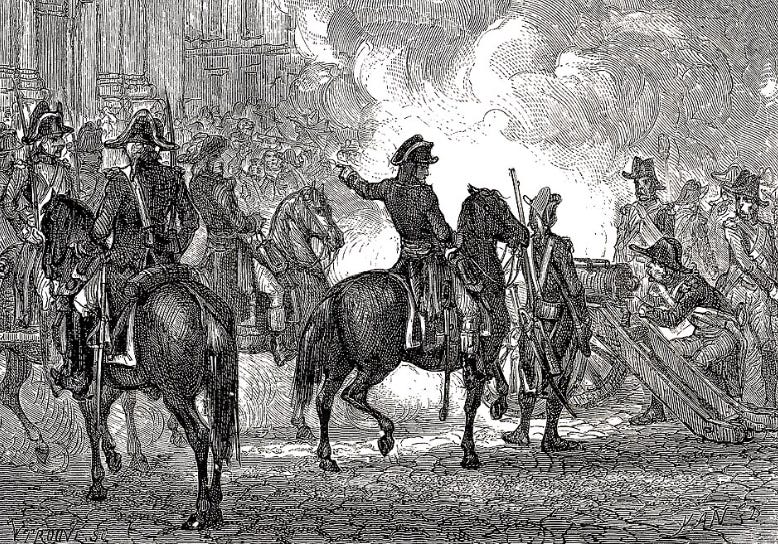

This is also why A Tale of Two Cities is the classical work of fiction for our time. Charles Dickens’ chief source for A Tale of Two Cities is Thomas Carlyle’s The French Revolution: A History, which lionized Napoleon for his willingness to fire cannons at a street revolt in 1795 Paris. Carlyle wrote that Bonaparte quelled the uprising with a “Whiff of Grapeshot,” where “the thing we specifically call French Revolution is blown into space by it.”

From here, Carlyle would go on to write On Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History, whose thesis is “Great Men should rule and that others should revere them.” Carlyle invented the “Great Man” Theory of History that is widely, and controversially, the basis for much of the teaching of history in American schools. For reasons that should be obvious, he is regarded by “People’s History” advocates as the intellectual founding father of Fascism—so much so that Goebbels’ diary says that he and Hitler were reading Carlyle’s biography of Frederick the Great in the Führerbunker.

From here, Thomas Carlyle

Corporal Bonaparte Ordered a Whiff of Grapeshot in the Streets of Paris, Which Thomas Carlyle Interpreted as Just a Great Man Doing a Great Thing for the Nation.

“Bonaparte Orders to Shoot at the Section Members” by Yan Dargent (1866), Which Appears in Adolphe Theirs’ Histoire de la Revolution—Published Five Years Before President Thiers’ Ordered the Army of the Third French Republic to Fire on His Fellow Frenchmen to Destroy the Paris Commune During The Bloody Week.

Lenin Literally Took Notes and Put This Theory into Practice During the Bolsheviks’ October Revolution and Won the Russian Revolution. Since the Whiff of Grapeshot, Every Dictator Raises the Specter the French Revolution to Justify Firing on Protesters in the Streets For the Good of the Nation.

What Sparked the French Revolution?

In May 1787, Royal Finance Minister Charles Alexandre de Calonne told the Assembly of Notables, the congress of high-ranking nobles and clergy, that King Louis XVI’s monarchy was so broke that major tax reform was necessary to keep France solvent. The Assembly couldn’t agree on a fix, so they called the Estates General, the “estates of the realm,” to consider reforms. In other words, the Enlightened nobles told the King that to raise revenue, he needed the consent of the people.

As discussed by Thomas Piketty’s hugely influential 2014 book (which grew out of the 2008 financial collapse), Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 1789 France suffered some of the worst wealth inequality in history: The top 10% held 90% of the kingdom’s wealth, and of that, the top 1% held about 60%.

Why? Louis XVI’s predecessors consolidated the realms of France by, mostly, exempting land-owning nobles and the Catholic Church from property taxes, leaving the vast majority of people with the smallest amount of wealth to finance the monarchy.

So, to satisfy the bankers, Louis XVI needed the assent of his subjects to levy new taxes. But when the Estates General wouldn’t ratify the King’s proposals, he locked the Third Estate (representing everyone but the nobles and clergy) out of the convention, triggering a revolt that resulted in the Tennis Court Oath, when representatives from all the Estates swore not to separate until Louis consented to a Constitutional regime.

From this moment, the feudal system started to dismantle slowly, then sometimes all at once, in kingdom after kingdom across Europe for the next two centuries. In its place rose different types of governments, the major movements being Democracy, Communism, and Fascism. These are, roughly, the same major movements that dominate today.

There’s an often misattributed 1972 quotation by Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai from a conversation with an American diplomat who asked, “What has been the impact of the French Revolution?” To which Enlai replied, “It’s too early to say.”

This is either wholly apocryphal, or more likely, a mistranslation about the 1968 student uprising in Paris.

Either way, it feels true because it is impossible to understand these three political movements without understanding the French Revolution. All of their various revolutionaries created and implemented their ideas based on their analysis of what began in 1787 Paris. Mostly, they looked at the same set of facts and drew wildly different conclusions–both infused by their contemporary politics, but also by developing their contemporary politics based on their historical analysis.

This is why the French Revolution’s historiography matters: Today’s historical actors are still acting in the traditions established by those who literally interpreted the French Revolution–then went out and changed the world based on their historical analysis.

Do you think the fall of the American Republic might be predicated on our enormous wealth inequality that’s the result of exempting the ultra-rich from paying their fair share of taxes?

That’s French Revolution stuff.

Do you think the specter of radical left-wing street violence so haunts reactionary centrists and conservatives that they would go to war with their own countrymen rather than institute wide-scale social reforms?

That’s French Revolution stuff.

And on and on. Once you study the French Revolution, you begin to see it everywhere in our politics.

A Rabble of Hungry Peasants Storm a French Prison Right Before Their Rent Is Due, and 156 Years Later, These Guys End Up at Some Crimean Resort Trying to Figure Out How to Defeat Hitler and Emperor Hirohito (Unknown Photographer; Churchill, Roosevelt, and Stalin at the Yalta Conference, 1945).

This Approach to the Historiography

The French Revolution is the most contested historiographical space, so we won’t cover close to all of it. Mostly, we will trace the development of Democracy, Communism, and Fascism from their French Revolution roots, with a narrow focus on the most important writers and historical actors. You may be surprised by how many names and ideas you already know.

Along the way, we will explain why certain historical sources and authors are important to A Tale of Two Cities, mostly confined to the final section on Thomas Carlyle and the philosophical underpinnings of Fascism. Armed with this historical knowledge, as we read A Tale of Two Cities, we will be able to understand:

1) How Dickens analyzed the causes of the Revolution,

2) How this understanding flows from Dickens’ view of human nature,

3) How this view of human nature informs his individual theory of history,

3) How Dickens’ Christianity flows from these views on human nature and history,

4) How these ideas can help us grapple with our current political moment, and

5) How to think deeply about all of it….because Dickens accomplishes, through fiction, what is beyond the scope of historians, philosophers, and politicians.

French Revolution Primary Sources

The French Revolution’s primary sources are, at once, very vast but with significant holes in the historical record. There are troves of open-access collections: My go-to is the Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media at George Mason University’s Liberté, Egalité, Fraternité, a free, curated, and peer-reviewed site supported by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

In written form, most primary sources are: 1) official government documents, 2) transcripts of speeches at national assemblies, 3) transcripts or reports of speeches given at political clubs, 4) journalism and pamphlets, 5) paintings and illustrations, 6) personal notes and diaries from famous figures, 7) letters written by eyewitnesses, and 8) maps that show the movement of events.

As for tangible objects, dozens of museums house French Revolution artifacts: In Paris, the main sources are the Musée Histoire de Paris Carnavalet, which recently underwent a four-year renovation to create an entire permanent exhibition of primary sources from the Revolutionary Era, from the Estates General to Fall of King Louis-Philippe during the Revolution of 1848. And the Panthéon, Paris’ monument to the Republic, where not only are the Republic’s heroes buried–but more importantly, its artwork conveys the mythology of the Republic.

Aside from the major museums, you can find interesting primary sources at small, niche places like the Musée de la préfecture de police (The Paris Police Museum). Below are my pictures of a restored National Guard uniform from the Revolutionary Era, an original peace-keeping order from the 1789, and a guillotine.

Sorry Everybody, It’s Only a Model Guillotine.

The Hole in the Primary Source Record: The Literal Voice of the Sans-Culottes and the Rural Peasantry

For me, it’s the voice of rural peasants and the Sans-culottes, the poor working class of Paris who did not wear fancy knee breeches–in their own voice.

Plenty of sources describe what the urban poor and rural peasants did, and plenty of letters, notes, and artistic renderings that give impressions of who they were. But rarely do you hear them in their own voice.

What’s often called “The Voice of the Sans-culottes” is, mostly, from the pens of politicians who claimed to represent them. These were the “salon radicals”: The (mostly) lawyers whose politics claimed to support the poor, and often did. In fact, most of the written primary sources are from these educated leftists.

But as for the people they claimed to represent, we really just rely on others’ impressions.

Even a book from the Marxist press like The Permanent Guillotine: The Writings of the Sans-culottes is, in its own description, “an anthology of figures who express the will and wishes of this nascent revolutionary class.” There were some middle-class leaders in the Enragés, the political faction representing the Sans-culottes during the worst of the Regin of Terror, including, for example, the priest Jacques Roux. But even he was college educated.

This makes sense: Many of the urban poor and rural peasants were illiterate–and, because paper was taxed, the actual working poor didn’t have the means to create records of their condition. In a haunting passage from A Tale of Two Cities, we will see that the rural peasants destroyed written records of their feudal obligations: Dickens imagines the peasant uprisings of 1793, in which rural peasants set fire to aristocratic mansions across France, creating a chaotic apocalypse straight out of Paradise Lost.

Perhaps the best example of this reflection of the poor’s voice is Jacques Hébert’s journal Le Père Duchesne. Hébert was a Revolutionary extremist who had extraordinary influence during the worst of the Terror. He was a member of the Jacobin Club in its most radical form, the Cordeliers Club that met in the most radical area of working class Paris, sat on the Paris Commune, which is largely responsible for the Insurrection of August 10th, the September Massacres, the Purge of the Girondins, and the Reign of Terror.

This Guy Was Just Mad As Hell and Not Going To Take It Anymore.

Le Père Duchesne was a fictionalized character that “voiced” the anger of the Paris working class, casting the Sans-culottes as the patriotic soul of the Revolution. Though he did not invent Duchesne, Hébert used his character to voice both the desires and the idealization of the populist Enragés, through this hard-working, salt-of-the-earth stove repairman. The conceit is genius: Because stoves are a luxury item, Duchesne has access to the homes of the aristocrats, so he simply reports and opines on the eccentric extravagances and casual cruelty of nobility.

This excerpt is representative of most Duchesne articles: His foul-mouthed bluntness is simply how the workingman talks, as opposed to those hypocritical rich dandies who barely lift a finger but eat four meals a day. Duchesne works hard, goes home to his loving family and thankful dog, over dinner telling his kids to always be loyal to the Republic and to cheer the guillotining of all their political enemies as traitors.

This is where Dickens’ fiction really does contribute to our human understanding of the Revolution. Duchesne is obviously a propaganda cartoon, a proto-vision of the German Volk in Nazi propaganda. In contrast, Dickens’ main characters in Paris, the Defarges, are his composite pictures of the Sans-culottes, but drawn with a complex human dimension.

In Contrast, Dickens Concluded That These Ladies from St Antoine, the Poor Neighborhood Near the Bastille, Had a Plan and Knew How to Pull it Off. Saint Antoine by Fred Barnard, Composed for the Original Publication of A Tale of Two Cities.

The Defarges hold the Enragés’ politics that for the new nation to live, the aristocrats must die. In Dickens’ telling, the Aristocrats v. the Sans-culottes turns into a kind-of race war, each side refusing to see the other as human. Yet, Dickens draws the Defarges not as idealized cartoons, but as literate, skilled, and strategic community organizers. They employ sophisticated methods to coalesce support in the Parisian underground–they are effective underground organizers who exploit the horrors around them to foment a Revolution. They are skilled politicians, even if they are never represented in any assembly.`

In one memorable passage, Dickens imagines the Defarges as a quiet, homely married couple sitting on the porch, wondering about the future after they’re gone–here, wondering if the Revolution will ever come in their lifetime. Madame Defarge tells her husband, take comfort my love, the Revolution comes like an earthquake after years of shifting earth underground, and then it arrives suddenly to do its destructive work. They even hold secrets from each other, with Dickens skillfully creating a portrait of people who, on some level, know what they’re doing is wrong, but social and cultural conditions force them to do it anyway.

In this way, when the Reign of Terror comes, we see the Sans-culottes as blood thirsty demons, as George Orwell said of A Tale of Two Cities. But by drawing them as humans who fall into this devilry, Dickens explains how extreme poverty and extreme wealth dehumanizes: The aristocrats are inhuman to create such conditions, leading the poor to become dehumanized themselves, and so the whole Revolution becomes this Hell between warring demonic factions.

This is why Dickens fills a legitimate gap in the early historiography of the French Revolution: Unlike Hébert’s cartoons, Dickens imagines a more human internal portrait of the Sans-culottes. He uses his novelist and journalistic skills to conjure the psychology of the St Antoine neighborhood during the 1790s, apart from the political propaganda of the far-left salon radical class.

The Wine-shop by Fred Barnard for the Original Publication of A Tale of Two Cities. Dickens Thought it All Went Off the Rails, But at the Beginning, The Defarges Were Savvy Community Organizers Who Suffered No Fools.