Part 5: Charles Dickens’ Sources for A Tale of Two Cities

Charles Dickens asked a very simple question that you can put on a bracelet: What Would Jesus Do?

How Did Dickens Get From That to This?

Because Charles Dickens’ source material was created by the proto-Fascist philosopher, does that mean that Charles Dickens was also a proto-Fascist, or that A Tale of Two Cities is a proto-Fascist book? Not really.

Thomas Carlyle’s Influence on Charles Dickens and A Tale of Two Cities

First, Dickens’ view of human nature, especially in his later career, leaves no room at all for the idea that a Great Man Will Come to Save Us. As George Orwell noted, in Dickens’ early career, to achieve his hit-making happy endings, rich guys showed up and showered everybody with money to make their problems go away. But as Dickens got older, and accumulated money in his own right, that “Good Rich Man” character tended to disappear. In A Tale of Two Cities, nobody is showing up to strong-arm the Reign of Terror to a halt. In fact, it ends well before Napoleon’s “Whiff of Grapeshot,” and as we’ll discuss…..Dickens just sorta skips right over all that Empire business.

Second, Dickens absolutely borrows from Carlyle’s conception of the “Bible of Universal History” and “Burning of the World-Phoenix” theory of history. But crucially, Dickens comes to the opposite conclusion of Carlyle. No spoilers, but as discussed, Carlyle concludes that charismatic leaders are the drivers of history, perhaps accidentally invoking Satan in Paradise Lost. Dickens is a deeply Christian man, unlike Carlyle, so he contemplates the Burning of the World-Phoenix according to the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

Dickens doesn’t ask, How does a Great Man create Order from Chaos? Rather, he asks, in the midst of apocalyptic chaos, what does following Christ’s example really look like? Yes, A Tale of Two Cities asks, What Would Jesus Do?

This is where I think Dickens’ reputation as a “popular” or, as Aldous Huxley wrote, “vulgar” writer is unfair. As we will painstakingly document, Dickens’ can bring all the Milton and Shakespeare allusions and deep historical understanding as well as a giant like Thomas Carlyle.

But for me, Dickens’ gift is to package this in compelling narrative, conveyed through striking visual poetry, with a “narration camera” that anticipates the grand epics of cinema, filling in the blanks between facts with convincingly human portraits–while contemplating the great questions of History and the Divine.

Dickens structures Cities somewhat on The French Revolution: A History, opening in pre-Revolution gathering of clouds before the storm. And Dickens borrows some of Carlyle’s poetic motifs, and descriptions of certain scenes, etc. Dickens reconceptualizes Carlyle’s first-person plural, present-tense muse-narrator as an all-encompassing God Tense narrator with, well, Charles Dickens playing the role.

For me, here’s what it comes down to: Dickens creates a moral treatise that asks why things got this way and what we should when it gets this way. In contrast, Carlyle created a roadmap for Fascists. Carlyle’s writing reads like… the work of a failed fiction writer with an exaggerated sense of his own genius, who is prone to unintentionally comic purple prose and unbearably pretentious over-writing. And Charles Dickens is one of the great prose stylists in the English language.

A Tale of Two Cities isn’t a melodrama stuffed into The French Revolution. It’s a treatise all its own.

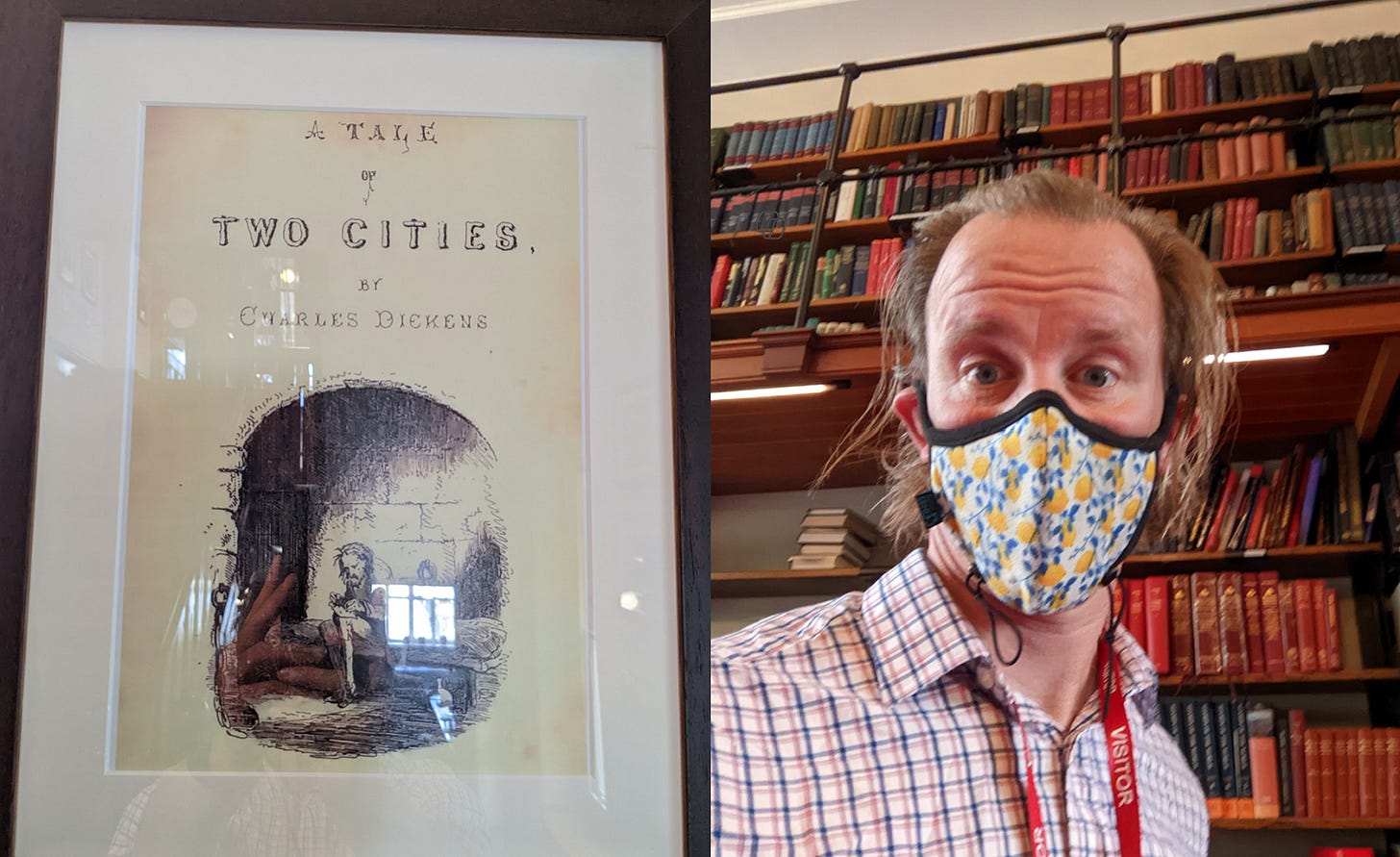

When You’re In the London Library During COVID, and You Find Their Copy of A Tale of Two Cities From an Original 1859 Publication.

But Let’s Not Forget Charles Dickens’ Colonialism, Racism, and Antisemitism

In the end, it must be said: Charles Dickens sent his sons to serve across the British Empire (the British Navy, East India Company, Bengal Mounted Police, Canada’s Northwest Mounted Police, Australia’s Parliament). He wrote to a friend that if he were the Commander in Chief in India, he would “do my utmost to exterminate the Race upon whom the stain of the late cruelties rested…and raze it off the face of the Earth.” And there’s plenty more that historians are grappling with, which was re-engaged after the George Floyd protests in 2020.

Dickens was an abolitionist who was shocked and scandalized by American slavery during his American tours. But he did join Thomas Carlyle and the racist reactionaries in The Eyre Case, involving the debate over whether the British Governor of Jamaica should have been prosecuted for killing or flogging over a 1,000 Blacks, and burning over a thousand of their buildings.

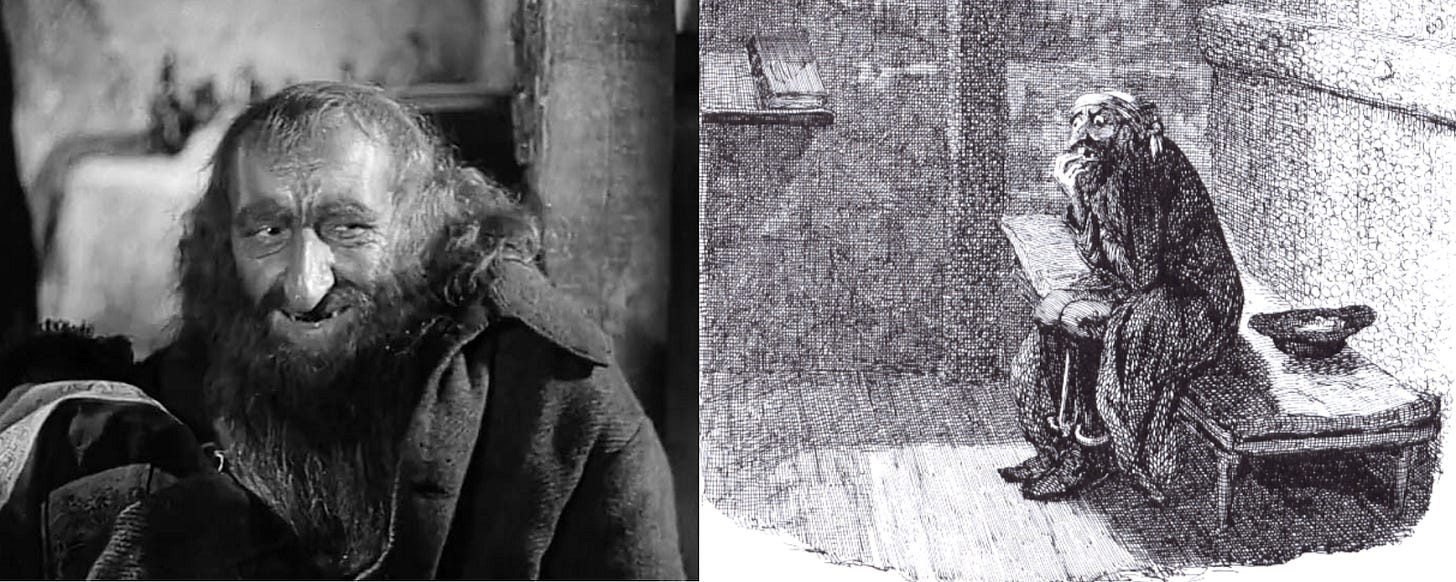

The original version of Oliver Twist is shockingly antisemitic to today’s ears–he refers to Fagin as “The Jew” 257 times. But when Eliza Davis, a Jewish woman whose husband bought one of Dickens’ homes, complained that he had “encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew,” Dickens stopped the printing of Oliver Twist to change the text, and later edited out Jewish stereotypes of Fagin and stopped doing antisemitic voices during public readings.

Or, in the most charitable light, Charles Dickens learned not to be antisemitic because he has Jewish friends now.

And, as we’ll talk about, the play in which he borrowed part of the Cities plot is an attack on the Inuit, accusing them of both sabotaging a failed English arctic exploration and for the cannibalism that was likely committed by the ill-equipped English themselves.

Long story short, I will write more about this later—it’s become the most discussed area of Dickens Studies in the Charles Dickens Society.

Alec Guiness’s Fagin in David Lean’s 1948 Oliver Twist Was Created to Look Like George Cruikshank’s Illustrations from the 1838 Publication. Jewish Activists Blocked Its Release in the U.S. Because it Seemed Wrong to Promote Antisemitic Stereotypes Three Years After the Liberation of Concentration Camps.

Other Sources for A Tale of Two Cities

A Tale of Two Cities is less “Based on a True Story” and more “Inspired by True Events.” Think of it this way: The “story” of Cities draws from the aforementioned Wilkie Collins play The Frozen Deep. The “true events” come from Dickens’ various French Revolution sources.

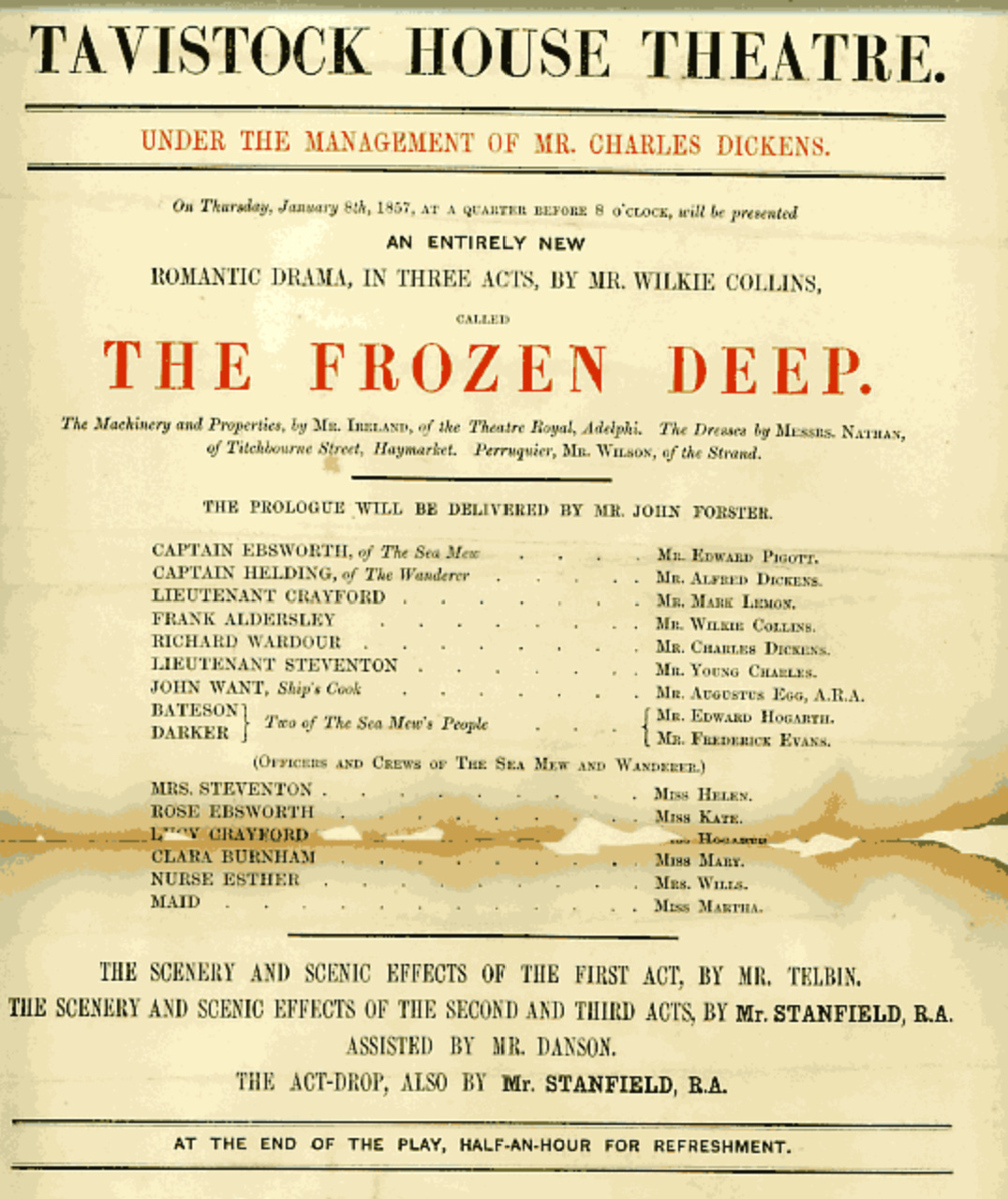

For now, I want to set aside Dickens’ construction of the main plot inspired by The Frozen Deep: Both because of potential spoilers, but also because of the enormous drama surrounding The Frozen Deep, even aside from the cannibalism-inspired native-savage plot. Dickens and Wilkie Collins were good friends and traveling companions, so much so that the Dickens Museum created a whole exhibition dedicated to them.

We will cover most this, but long, long story short: Dickens starred as the leading man in The Frozen Deep, his marriage was falling apart because his wife had ten kids and spent most of her adult life pregnant, so he became infatuated with an eighteen year old he shared the stage with, carried on an affair, sued his publishers who wouldn’t publish his letter regarding the allegations, tried to have his wife committed, went through a public divorce, got in a trainwreck (literal one, not figurative) that he fled so his mistress wouldn’t be revealed.

The legendary academic Claire Tomalin found the receipts and documented the whole thing in The Invisible Woman, which was adapted into a movie with Ralph Fiennes as Charles Dickens. It’s really all just too much for us now.

Charles Dickens Played the Lead, Then Partook of a Half-an-Hour of Refreshment

As for the true events, in a letter to Carlyle, Dickens asked for sources specifically about ordinary lives in France, and within two weeks, “two cartloads of books” were delivered to his house from Carlyle’s London Library. Knowing Dickens, he probably exaggerated this to preempt accusations of historical inaccuracy, but he does seem to have aligned his fictional plot to Carlyle’s telling of historical events. Still, Dickens leaves out many “set pieces” of the Revolution: The Flight to Varennes, Louis XVI’s execution, and others. He selects other events (the Women’s March to Versailles and the September Massacres, most notably) as ways to advance the personal story that happens within the Revolution.

For those steeped in the Revolution’s history, Dickens’ narrative is disorienting: The relatively short time between the book’s opening at the Storming of the Bastille feels shorter than it was, but then the climactic piece during the height of the Massacres and the Terror feel much longer than it was. To give Dickens the benefit of the doubt, this feel of the passage of time was, likely, what people experienced: The September Massacres only occured for four days, but they were the longest four days of any Parisian’s life.

Other researchers have dug into the particulars of what was on Dickens’ bookshelf at his various houses (he seems to have swapped one copy of Carlyle’s book for another at one point), and what Carlyle might have pulled off the shelves of the London Library, which he likely footnoted in his own book.

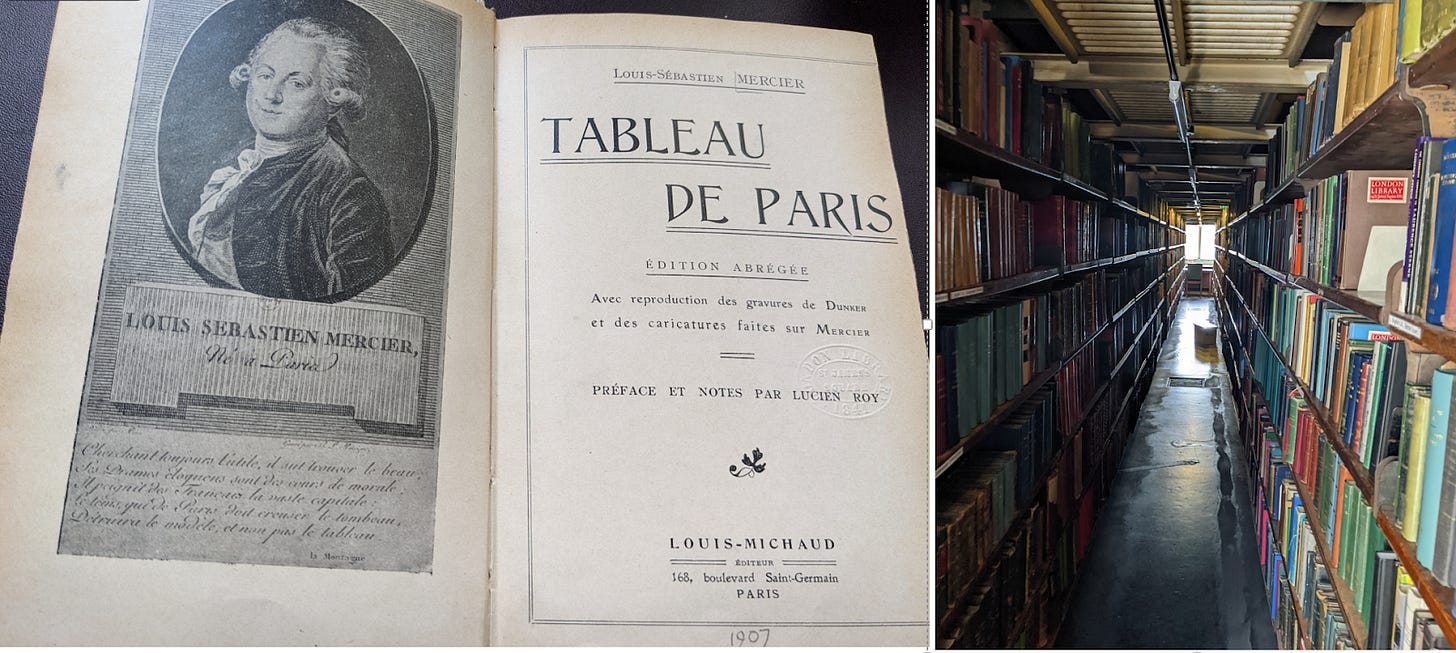

This leads us to Louis-Sébastien Mercier’s twelve-volume work Le Nouveau Paris (1797) and Tableau de Paris (1788). The stories of the Monseigneur’s ostentatious chocolate, the out-of-control carriage of the Monsieur de Marquis, the traumatized Dr. Manette, and others seem drawn from details in these books–and in some cases, Dickens directly lifts paragraphs of details to construct scenes and portraits.

The Author’s Pictures From Deep Within the Stacks London Library, Founded in 1841 by Thomas Carlyle, Author of The French Revolution: A History and Charles Dickens’ Primary Source for A Tale of Two Cities. I Eventually Found a Source for the Source, Louis Sebastien Mercier’s Tableau de Paris, But Unfortunately, It Isn’t Carlyle’s Copy

Dickens’ Methodology

As far as we can tell, Dickens had a main plot in mind, and a few subplots, and needed actual events and eye-witness accounts to build out the entire multi-dimensional narrative. He read Carlyle and Mercier and Rousseau and a few other volumes (doesn’t seem to be “two cartloads” of sources), and with his novelist’s eye, picked out some colorful details and anecdotes to build scenes. From here, he built characters out of these scenes, then stitched these characters into this grand narrative. If you understand A Tale of Two Cities as a prestige tv limited series, with each episode focused on specific characters or places, then brought together in the final episodes, that’s what Dickens does.

This is why, I think, Dickens’ overall interpretation of events is convincing: He used the same types of sources as many later historians. Dickens was criticized for “not being a philosopher” or whatever, but he seems to have done as much homework as needed to create a narrative. A Tale of Two Cities’ genius isn’t that it’s a comprehensive history, but it’s a deeply human impression of the terror: Think of it more as a series of slice-of-life sketches–the kind of writing that made Dickens’ career–than a twelve-volume magnum opus. For reference, to prepare for my own trip to the London Library, I used J.A. Falconer’s “The Sources of A Tale of Two Cities” and Andrew Sanders’ “‘Cartloads of Books’: Some Sources for A Tale of Two Cities.”

The Plagiarism Scandal

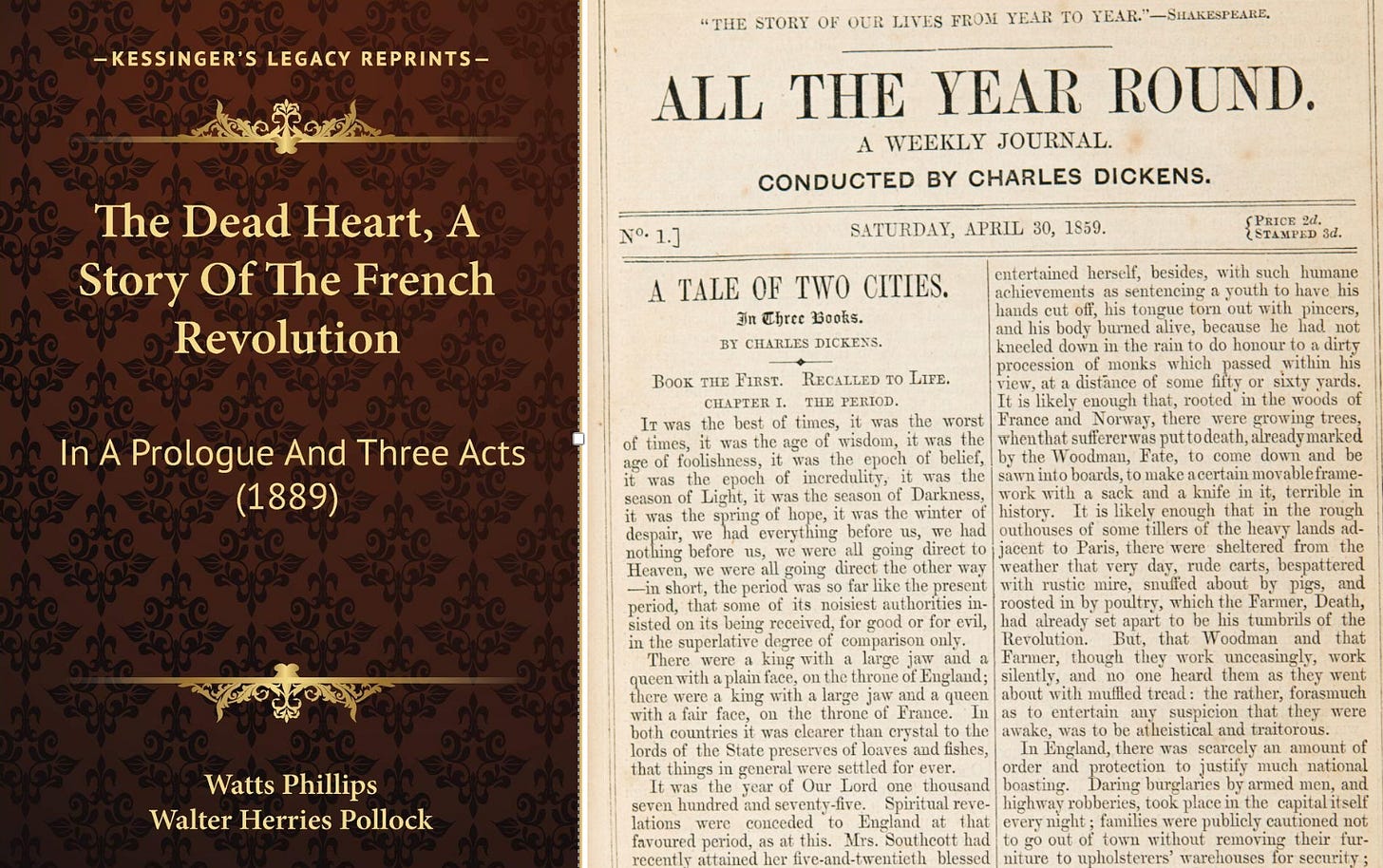

One final note: Dickens might have plagiarized the plot from a play staged in London in 1856, two years before he began working on Cities. Watts Phillips’ The Dead Heart is also set in the French Revolution, beginning in 1771, a man gets thrown into the Bastille via lettre de cachet, when he’s released his brain is broken by the experience…the plots are so closely drawn that it can’t be coincidence. And even though Phillips’ work was produced well before Dickens began work, it was the less-famous Phillips who took the plagiarism accusation.

Entire articles and investigation have tried to unravel this, and most Dickensians conclude that Dickens didn’t plagiarize from Watts, but they relied on the same sources. For me, it seems a bit convenient that Watts and Dickens would have drawn from the same details in Carlye’s and Mercier’s works to create very similar plots. And, we know that Dickens was an avid theatergoer, fancied himself an actor himself, so it seems possible that he would have attended Watts’ play, or at least been told of the plot.

I can put together the story like this. This was an extremely chaotic period in Dickens life: Feuding with his publishers, scrambling to pay for his large family and extravagant lifestyle, decades of workaholism shredding his nerves, growing disillusioned with his wife, and then, needing a hit, taking a big swing by concocting a sweeping historical fiction based on the French Revolution. He’s got a seed idea for a plot, but needs to plant it in the history. Then his buddy Carlyle dumps two cartloads of books at his house while he’s also running charities, lobbying Parliament, and starting up his own literary magazine.

And now you see this play from a much less famous writer that’s already started the seedling. So you dig it up, plant it in your own book, figuring that, now that it’s on the estate of the famous Charles Dickens, it’s your tree now. I can prove that, nobody has, but I can see how Dickens would have gotten there. We’ve all been tempted to cheat on our homework when we don’t feel like we have time to do it.

They Had a Lot in Common!

Ok, now that we’re finally to the end, remember that all this is important to our discussion of the book. We will tackle:

1) How Dickens analyzed the causes of the Revolution,

2) How this understanding flows from Dickens’ view of human nature,

3) How this view of human nature informs his individual theory of history,

3) How Dickens’ Christianity flows from these views on human nature and history,

4) How these ideas can help us grapple with our current political moment, and

5) How to think deeply about all of it….because Dickens accomplishes, through fiction, what is beyond the scope of historians, philosophers, and politicians.