Part 2: The French Revolution's Contribution to Democracy

Today's Concept of the Political Left and the Political Right Literally Came From the First English Debate About the French Revolution

Part 2: The French Revolution’s Contribution to Democracy

Figuratively and Literally on the Left is Thomas Paine, Figuratively and Literally on the Right is Edmund Burke. Their Debates Over the French Revolution Created Today’s Political Left and Right.

The Great Democratic Debate of Constitutional Monarchy v. Republic: Edmund Burke v. Thomas Paine

Burke and Paine were not so much historians of the Revolution as actual participants. Edmund Burke was a legendary MP who deeply influenced Britain’s foreign policy towards Revolutionary France while the Reign of Terror was happening. Thomas Paine not only sparked the American Revolution with Common Sense, but later joined the French Revolution and ended up in a Paris prison during Terror, spared from the guillotine only by a clerical error inside the prison and was released in the general amnesty following the Thermidorian Reaction against Robespierre.

Their vicious, public debate about the French Revolution is, literally, where the political terms “Left” and “Right” come from. Inside the first French National Assembly after the Tennis Court Oath, the more radical, anti-monarchy members sat to the left of the President’s chair, and the more traditional members sat to the right. This physical description was used to shorthand the basic dispositions of Burke and Paine.

Edmund Burke is widely considered the Founding Father of Conservatism, Thomas Paine the Founding Father of Progressivism. So, yes, the fundamental dispositions of today’s politics is directly born out of contemporaneous analyses of the French Revolution. For more, I highly recommend the indomitable Stephen West’s Philosophize This! episode “Are You Left or Right?”

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke is still today a primary source for British Tories and American Republicans. He believed that virtue is the foundation for society, that institutions–religious, government, business, and otherwise–were necessary for the “moral stability” of the nation. So, for Burke, social change must be incremental, that radicalism is per se immoral and indefensible, no matter what ideals or material conditions the radicals advocate for.

To this end, Burke actually supported America’s grievances against King George III and Parliament, opposing the use of force in the colonies. Burke did not support American independence, but he did propose a resolution to allow the Americans to elect their own Parliamentary representatives and create a General American Assembly. Burke sympathized with the Americans because he saw British policy as incredibly disruptive to their established patterns of taxation and governance. The policy wasn’t conservative.

As for the French Revolution, Burke’s Reflections on the Revolution in France was the defining intellectual argument against the Revolution–so much so that Louis XVI himself had it translated into French. Today, it’s regarded as the founding document of conservatism, arguing for traditionalism, in all its forms, as the political philosophy that facilitates national virtue:

Society is indeed a contract…but the state ought not to be considered as nothing better than a partnership agreement in a trade of pepper and coffee…to be dissolved by the fancy of the parties. It is to be looked on with other reverence…It is a partnership in all science, a partnership in all art; a partnership in every virtue, and in all perfection….it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.

Burke’s preferred governance is gradual reform under a Constitutional order based on traditional principles, held together by a king and administered by an aristocratic elite. Revolution in the name of “abstractions” like “liberty” and “rights” are too speculative, and so will be defined by the regime of the day to justify its inevitable tyranny. Only rights that are “inherited,” justified by “antient” constitutions and established by tradition, can form the basis of a virtuous nation.

Engraving (1851) of Sir Joshua Reynolds’s “The Club,” Where Edmund Burke (Front Center, Red Coat) and the Boys Agree That National Stability Is Only Protected When the King Asserts His Godly Command to Rule Over the Rabble.

Thomas Paine

Reflections sparked a “pamphlet war,” first with legendary feminist Mary Wollstonecraft (mother of the future Frankenstein author Mary Shelley), who wrote A Vindication of the Rights of Men, in a Letter to the Right Honourable Edmund Burke; Occasioned by His Reflections on the Revolution in France. Basically, she called Burke a sexist, aristocratic toady for the King and the Church of England. Wollstonecraft extended these arguments two years later in her seminal work, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman.

Second, Burke prompted a two-volume response by Mary Wollstonecraft’s acquaintance, who ran in the same intellectual circles as her future husband William Godwin, the Englishman turned American Thomas Paine. Yes, that Thomas Paine, whose The Rights of Man: Being an Answer to Mr. Burke’s Attack on the French Revolution is one of the founding documents of modern progressivism.

Thomas Paine is most known to us as the author of Common Sense, which rallied American patriots to the revolutionary cause. But Paine is much more than that: Born and worked as an Excise Officer in England, he racked up debts, divorced his wife, somehow met Benjamin Franklin, who got him on a boat for Pennsylvania, where he wrote magazine articles denouncing slavery and advocating for an American republic, was dispatched to Paris to lobby for French funding of the American Revolution, moved back to England where he wrote Rights of Man, which got him indicted for seditious libel, prompting him to flee to Paris, where we was elected to the National Convention of the French Republic, got thrown in prison and nearly guillotined, met Napoleon (who claimed to sleep with a copy of Rights of Man), moved back to America and feuded with George Washington, dying in Greenwich Village in 1809, had his bones dug up to be given a hero’s burial back in England, and still today people claim to own pieces of his skull.

So, what did Paine write to Edmund Burke that got him indicted for seditious libel?

Primarily, that hereditary government is incompatible with individual liberty.

Burke argued that centering society on a monarch creates stability, with a small ruling class lording over the poor. For Burke, private property and lawful inheritance are the mechanisms of that stability: the ruling class bequeath their property and titles to their sons, who are trained in the art of good governance of the people. Thus, the wisdom of the ages is passed down through the educated class such that government itself is a “contrivance of human wisdom.”

Paine said this was a weak defense of feudalism, which was dying with the rise of Enlightenment ideals. As such, he dedicated Rights of Man to the great founders of the American and French Revolutions: George Washington, who refused to become emperor and willingly gave up power to establish the democratic republic; and Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, who renounced his aristocratic title in Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen.

To answer the Political Question, Paine argued that human rights originate in nature. They are not a benevolent gift bestowed by a divine monarch–nor are they granted by political charters, which implies that they can be revoked. That which comes from nature cannot be taken by man.

What does this mean for constitutions? Each citizen enters into a contract with each other to “produce a government,” which safeguards inalienable, natural rights. So, the only legitimate governments arise from the consent of the people from below, not monarchs from upon high. This requires the complete eradication of hereditary government and noble titles.

To answer the Social Question, Paine argues that poverty deprives you of individual liberty, so any government that allows crippling poverty undermines its own legitimacy. So, social welfare is a natural right, not charity–he harshly criticized England’s Poor Laws (the main target of Dickens), saying that any government that allows its citizens to suffer poverty violates their natural rights, not just because of the poverty, but through the infliction of workhouses, debtors prisons, and the death penalty.

Thus, Paine advocates for the redistribution of lands and wealth, as well as tax reform and public education. Of these, Paine agrees with Burke, saying that education is the most important, but for a completely different reason. Rather than hoarding education for a small ruling elite, Paine says that all citizens should learn the Enlightenment principles that make democracy possible, and that education is the means by which individual citizens escape the cycle of poverty that oppresses their natural right. Monarchs and titled nobles, he says, are incapable of carrying out such a program because education is what gives them power, land is what gives them serfs, inheritance hoards their wealth, and they will never institute the tax reform to provide the means of the social welfare that is everyone’s natural right.

So that’s why Rights of Man was seditious libel: Though Paine never outright says, “Overthrow King George III,” he “suggests” a written constitution deliberated by a far more democratic body than the British Parliament, the elimination of aristocratic titles, a progressive income tax that would break the feudal system, and replacing the Poor Law with subsidized public education.

Rights of Man was a political document for its times, with a whole bunch of specific proposals for the government, which, truth be told, do not completely add up. But its enduring legacy is as a defense of the French Revolution’s declaration of a republic, laying out a progressive vision of government to counter the conservative Burke.

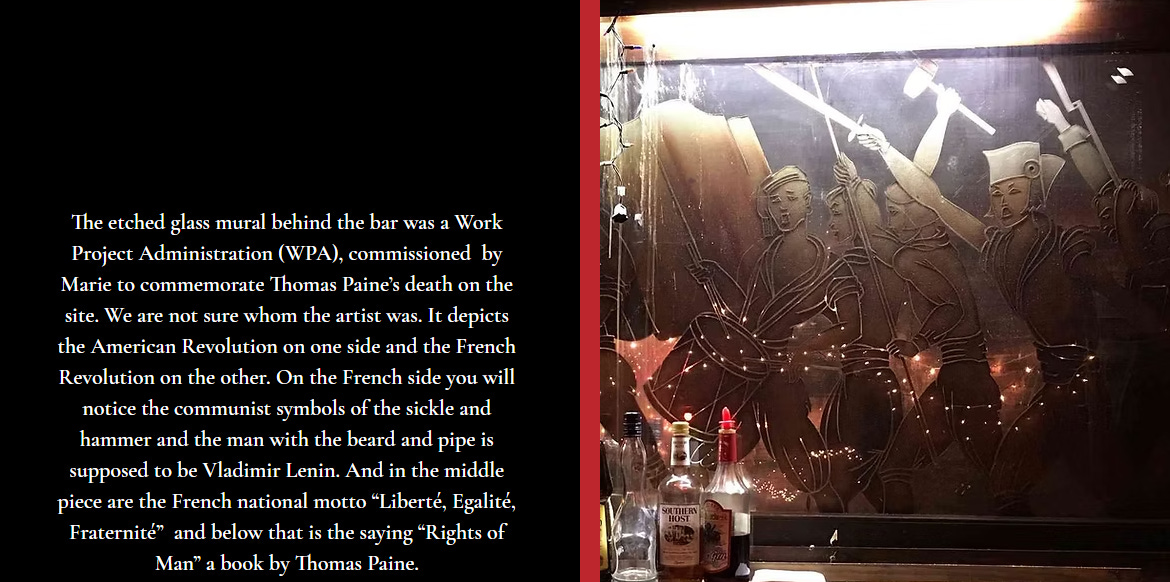

Marie’s Crisis Cafe, Around the Corner From Stonewall in Greenwich Village, Today is a “Broadway Showtunes ‘Sing-Along’ Piano Bar.” It’s Built on the Site of Thomas Paine’s Last Home, Where He Died in 1809.

Behind the Bar is a WPA Mural of the American and French Revolutions, With an Homage to Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man.

As for Dickens, he will agree neither with Burke nor Paine because of his views on human nature. Dickens certainly does not believe in any sort of humane, enlightened monarchy or church. But neither does Dickens believe that institutionalized education or democratic governments will make things better. Dickens believes that human nature is evil: We are all born sinners, so whatever form of government you dream up is going to be corrupt because human beings are corrupt. This is key to understanding the turn of A Tale of Two Cities in the third act.

The Liberal, Democratic Reformers: François Mignet and Adolphe Thiers

These next two writers worked after the fall of Napoleon, during the Bourbon Restoration and the July Monarchy of King Louis-Philippe, France’s “bourgeois” monarchy that lasted from 1830-1848. They championed the “liberal nobles,” the enlightened aristocrats who understood the need for reform, some of whom like the Marquis de Lafayette, crossed the Atlantic to fight in the American Revolution.

François Mignet’s Histoire de la révolution française (1824) was the first comprehensive history available to the general public, selling an incredible 200,000 copies. Mignet was from the Vendée region along the Atlantic coast, a conservative royalist region that erupted in civil war during the Revolution and experienced the bloodiest of the Terror. So, Mignet’s analysis is that both the conservative royalists and the Jacobin republicans were too extreme. Thus, the liberal nobles who advocated for the Rights of Man, but without overthrowing the entire social order, were the enlightened men of France.

In Mignet’s telling, men like the Marquis de Lafayette are the heroes of the “First Revolution” of 1789, which enshrined rights in France’s political order. The “Second Revolution” of 1793 was led by the villains, where men like Georges Danton, Maximilian Robiespierre, the radicals of the Cordelier Club and the Enragé, attempted to overthrow the social order, descending France into the bloody chaos that Mignet’s father experienced in the Vendée.

Mignet didn’t advocate for a republic: he was a constitutional monarchist who used his stature as historian of the revolution to advocate for the Duke of Orleans, Louis-Philippe, to rule as “King of the French” after the fall of his absolutist Bourbon cousin Charles X in 1830.

Here’s where Mignet’s analysis of the French Revolution had a very real impact on world history: Mignet deeply influenced the man he worked alongside, Adolphe Thiers, who published his own 10 volume history of the French Revolution in the 1820s. This was a radical act for both Mignet and Thiers: They interpreted the French Revolution’s heroes as the liberal nobles, who staunchly opposed the absolutist Bourbons who were restored after the fall of Napoleon.

This bravery gave Mignet and Thiers political credibility during the Revolution of 1830. Mignet, mostly, stayed a historian until he died in 1884 at the age of 87. Thiers, though, embarked on a long, consequential political career that lasted through the July Monarchy (serving as Prime Minister twice), the Second Republic, the Second Empire, eventually becoming the President of France during the Third Republic in 1871.

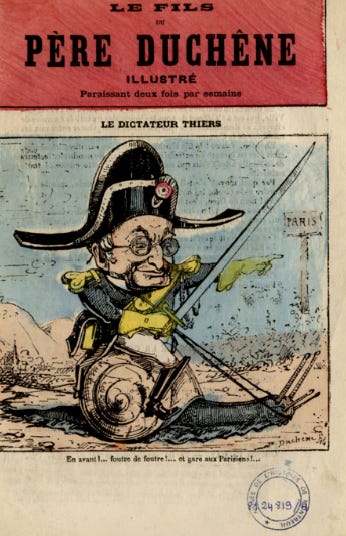

A Paris Commune Pamphlet Reviving Jacques Hébert’s journal Le Père Duchesne, Depicting “Le Dictateur Thiers” Riding a Snail. The Communards and Thiers Both Understood Themselves as Acting as Direct Descendants From the First French Revolution.

When he held power, Thiers put his analysis of the original Revolution into practice: After Emperor Napoleon III was captured during the Franco-Prussian War, Thiers headed the Government of National Defense and was forced to negotiate a humiliating peace with Otto von Bismarck in the Palace of Versailles. After the National Assembly voted for the armistice, Thiers embarked for Paris, but the working classes of the city–who made up most of the National Guard–had radicalized into a socialist movement.

Long story short, Thiers chose to wage war against his own capital to stamp out the Paris Commune radicals looking to overturn the social order and create something entirely new. In this regard, Thiers’ legacy is The Bloody Week—and, important to world history, the Paris Commune was the last revolutionary uprising of Karl Marx’s time. Marx’s analysis of the Thiers and the Commune deeply influenced a young Vladimir Lenin, who would not make the same mistakes as the Commune when the Bolsheviks seized power in 1917.

It’s fair to say that, in this moment, Thiers chose the violence that his liberal noble heroes of 1789 did not, that King Charles X in 1830 did not, that King Louis-Philippe in 1848 did not, and they all ended up in exile or guillotined. Thiers’ choice to crush the Paris Commune was deeply analyzed by Lenin in his study of the French Revolution, creating a roadmap for the Communists after the fall of Czar Nicholas I’s Russian Empire and the Provisional Government in 1917.

The Rue de Rivoli After the Bloody Week and the Fall of the Paris Commune (1871). Echoing Maximillian Robespierre’s Admonition “Did You Want a Revolution Without A Revolution?”, Adolphe Thiers Was Willing to Stop Another Reign of Terror By Doing a Reign of Terror. Lenin Took Notes.

The Bounds Between Democracy and Communism: François Guizot and Jules Michelet

Before we tackle the Marxists, we will backtrack to a man specifically namechecked in the very first paragraph of The Communist Manifesto, François Guizot. Similar to Thiers, François Guizot began professional life as a historian, parlaying his prominence into a long, consequential career in French politics, spanning the July Monarchy’s Revolution of 1830 to the Revolution of 1848 and the Second Republic.

Guizot was born in 1787, and during the Napoleonic Era, he became a writer and minor bureaucrat. During the Bourbon Restoration, Guizot was in and out of government, eventually settling into an appointment at the University of Paris. There, he published long treatises on representative government, focused less on France and more on Great Britain and its revolutions. In this, he originated the concept of the “History of Civilization,” the idea that, over time, nations create the institutions that are “necessary to uphold their emancipation.” Something like a theory of “total history.”

Guizot was a staunch institutionalist because, well, his father was guillotined during the Reign of Terror in 1794. Guizot is best described as a conservative-liberal: Absolutely opposed to the radicals who executed his father, but also of the opinion that absolutists, whether in the vein of the Jacobin Radicals or Napoleon Bonaparte or the Restored Bourbons, could never bring a nation stability because they provoked those same radicals. So, Guizot favored “a monarchy limited by a limited number of bourgeois.”

Long story short, Guizot’s philosophical underpinning made him popular with King Louis-Phillipe, but Guizot was too much of an academic to really understand practical politics or good governance. Ultimately, his Prime Ministership doomed the July Monarchy in 1848. Guizot was incapable of reform when, clearly, some compromise for expanding the vote for Parliamentary elections was necessary. Louis-Phillipe listened to Guizot for too long, and eventually the streets of Paris rose up in revolt. Guizot’s resignation caused much celebration, but it wasn’t enough.

Over the course of three days, blood was shed across the city, with revolutionary National Guards closing in on the Tuileries Palace. Adolphe Thiers advised the King to escape Paris, then lead columns of regular troops into Paris to crush the revolt. But Louis-Phillipe didn’t have the stomach to fire on his people and destroy this great city. He abdicated and fled to England. Twenty-three years later, Adolphe Thiers would prove that he did have the stomach for it.

Guizot, on the other hand, retired from public life and went back to writing. When he analyzed the rise of constitutional monarchy in England and republicanism in America in Discours sur l’histoire de la Revolution d’Angleterre, he found a people building institutions that would settle the peace and provide prosperity. To Guizot, France and Europe had not settled the History of Their Civilizations, which is why they lagged behind their English-speaking brethren.

In his analysis of the rolling series of French Revolutions, which guillotined his father and nearly strung him up in the streets, Guizot concluded that the toppling of French institutions, rather than reforming them, never gave France a firm enough foundation on which to build a great nation.

Guizot’s analysis is obviously self-exonerating, even if it might be persuasive. The truth is that he practiced government like an academic: the historian subsumed the statesman. He spent so much time and energy legitimizing the constitutional monarchy of King Louis-Phillipe that he didn’t develop the skill of practical government or an ear for politics.

In the end, Guizot so mishandled a simple non-crisis that it brought down the monarchy: Les Campagne de banquets. The Banquet Campaign was, really, a trolling exercise by the moderate liberals: Guizot’s cabinet became more authoritarian, aggressively enforcing the law prohibiting “public assemblies,” so liberals sponsored private dinners that properly toasted the King, but were really an excuse to organize and denounce the monarchy. Rather than relent one inch, Guizot called in the police and military to stop a Paris banquet from celebrating the international icon of democratic republicans, George Washington, triggering a riot that conflagrated beyond his ability to handle.

A minor figure during this era of academic and intellectual repression was Jules Michelet, the Chair of the History Department at the Collège de France. Michelet secured this position after working under the traditionalist historian…François Guizot, then part of the Literary Faculty at the College de France.

As an academic, Michelet was devoted to Enlightenment ideals–appropriating the old art criticism term “Renaissance” in his Histoire de France to describe the wholesale modernization from the Middle Ages, when mankind was “reborn.” He was a staunch republican whose work contributed to the radicalization of students that led to the Revolutions of 1848. In fact, the cancellation of his lectures on January 2nd, 1848 led to a large-scale student demonstration against King Louis-Philippe and Guizot, the momentum of which morphed into the Campagne de Banquets.

Michelet is the great democratic republican of the early French Revolution historiography, who today would be classified as a democratic socialist, becoming such a popular teacher that he triggered demonstrations against his stodgy former boss who wanted everybody to sit down and shut up.

François Guizot Accepts the Charter of Government From “Citizen-King” Louis-Philippe I (1830). The Foundation Wasn’t Deep Enough to Hold Up the House of Orlean, But Guizot Didn’t Do Much to Buttress the Supports. Marx and Engels Predicted as Much, and Wrote The Communist Manifesto.