How Literature “Lives”: Each Reader Gives It New Life in Their Own Time and Place

If It Wasn’t the Most Important Subject In School, They Wouldn’t Be Willing To Kill Over It

Living Literature’s Guiding Light: Supreme Court Justice and Musical Theater Nerd Ketanji Brown Jackson, Seen on the Right in Her Broadway One-Night Only Appearance in “& Juliet.”

Part One. The Origin Story “Living Literature”

"Living Literature" is the culmination of my 25 years inside the high school classroom and the courtroom. As I've transitioned from teaching my own classes to training teachers on how to teach, I've thought a lot about why we read and teach literature:

Revitalizing the Humanities is Essential for Saving Democracy.

“Living Literature” is an ongoing project to rethink the reading and teaching of Literature. For casual readers, this will be me guiding you through great works of Literature for your enjoyment, that if you invest the time in a Great Book, I will help you get the most out of it. The point is to be fun, like a book club led by your favorite teacher.

For teachers, this is about the teaching of Literature. For over twenty years, my rather non-traditional career was, nonetheless, spent almost entirely inside the classroom with students. In this laboratory, I developed a particularly critical thinking- and historical thinking- based methodology, which I grounded in theories of Constitutional Law, to bring the Great Books of the Past into the Present. To do that magical thing they tell us we should be doing, but then get really mad when we actually do it: Make Literature Relevant For Our Students.

There’s multiple strands to this, which I will bring together into, hopefully, a methods book for teaching Humanities in the Age of AI. For now, I’ve adapted all this into a curriculum design and teacher coaching practice, focused on infusing intentional rigor into the teaching of Humanities.

With that, let’s go on a journey to understand how Literature Lives.

The Problem With Teaching Literature in American High Schools

If you’ve ever read a book that really changed you, that helped you find your purpose, understand this:

The Standardized Testing Regime actively discourages high school teachers from creating that experience for you.

Why?

High-stakes standardized testing creates a teaching of literature that's designed to obscure how literature helps us understand the present. It flattens literature into boring exercises about “textual analysis” to help you “find the author’s purpose.”

Great teachers can still make books come alive, but it cuts against our training and incentive structure, and there’s virtually no guides for teaching teachers how to make literature “relevant.” Because the tests have to be “standardized,” we teach you to interpret text in a one-dimensional way designed lead you to the “correct” answer. We’re taught to help you find the author’s purpose, not yours!

This has been the dominant mode of literary interpretation since the 1920s, when the Humanities abandoned its Liberal Arts roots and adopted the methodologies of Modernism and the Scientific Revolution. Combine that with the fact that since at least the 1990s, nearly all investment and energy in secondary curriculum has been directed at STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Mathematics). Thus, the entire practice has become so stagnant that, frankly, the Humanities haven’t developed a great answer to the question, “What is the point?”

This gap is what Living Literature will try to address, from how the Humanities teach more rigorous critical thinking skills than STEM fields, how the cultural and philosophical “soft skills” are actually the employment skills of the future, and how Humanities is the essential discipline for a democratic society.

Living Literature will take literature seriously as an object worthy of study, applying historical thinking and other critical thinking skills to use literature not just to understand the past, but to comprehend the present and think about the future. I will define and flesh out the methodology in future posts. The point of this article is to articulate exactly why the Humanities Are Taught Like This, and a Brief Glimpse Into How We Can Do It Better.

Honestly, The Best to Ever Do The Job. We’ll Explain Why.

They Tell You How to Think: Law School Actually Teaches Lower-Order Critical Thinking Skills Than the Humanities

I began professional life in a rural Southwest Missouri high school as a sophomore Language Arts teacher and a high school gifted program coordinator. As part of gifted certification, you dig deep into theories of learning. Gifted training asks you to think about thinking: When we say “critical thinking,” what exactly do we mean? I studied Bloom’s Taxonomy and used the little Verb Wheel to create rigor in my classroom….but I was just some high school teacher, and when you start out in this profession, you can begin to internalize the deficit narrative our society imposes on teachers.

So, when I left education for law school, I thought that this would be where I would really learn how to think! That’s what they tell you!

What I found was that, compared to studying literature and teaching kids explicit critical thinking skills, legal reasoning is actually quite formulaic and, truth be told, very limited. You learn a rule, you apply the rule to the facts, you reach a conclusion: The IRAC Formula!

This is pure analytical reasoning, which, on Bloom’s Taxonomy, is a lower-level critical thinking skill. Legal reasoning does get more complex, but mostly, the methods are divorced from the complexity of the historical, moral, and ethical dimensions of literature. This is intentional: As documented by Dylan Penningroth’s Before the Movement: The Hidden History of Black Civil Rights, legal educators literally edit out racial and other social context from cases reprinted law school textbooks, presenting “The Law” as if it’s an objective, abstract thing wholly separate from its social and cultural context.

This is how they teach you “what the law is.” These rules exist outside of classism, racism, sexism, all the '-isms. Then you apply the “relevant” facts to this abstract, apolitical concept—which, because the concept is abstracted from social and cultural context, the power dynamics of classism, racism, sexism, etc. aren’t actually “relevant.” Those ground rules laid, after a series of arguments, the judge makes a decision based on pure reason.

Obviously, this isn’t how the law works at all, but that’s mostly how it’s taught. It’s vital to the prestige of the profession that The Law is objective and reasonable, that it floats above social context, cultural power dynamics, economic conditions, forms of discrimination—otherwise, it just begins to look like the grubby business of politics dressed up in suits and robes. I mean, that’s why they wore wigs!

The Author on a Charles Dickens-Themed Study Abroad Trip With High School Students, in Front of Stanley Ley on Fleet Street in London, Trying to Figure Out If I Could Pull Off the English Barrister Look

Constitutional Law: The Humanities of Law School

Constitutional Law is the closest that law gets to the values-based complexity of philosophy, history, or literature. But even then, the two current dominant schools of Constitutional thought, Originalism and Living Constitutionalism, still seek to “objectively” say what the law is, without creating a values-based framework of what it should be. Still, Con Law was the only course I recognized from my teaching career.

No joke, it was Charles Dickens who convinced me to leave my law job with a district attorney and return to the classroom. I spent most of my day deciding who goes to jail and who pays a fine and who gets their case dismissed. In short order, I came to understand myself as a legal functionary facilitating a debtors’ prison, like a minor character out of Bleak House or Little Dorrit or Oliver Twist.

There often wasn’t a lot of judgment involved–mostly, people’s fate was based on their ability to buy themselves out of mistakes. Justice was arbitrary, or as Oliver Twist’s Mr. Bumble observed, “the law is an ass–an idiot.” And I felt being a lawyer was making me an idiot.

Turns out, the real smart people stuff was what I was doing, teaching literature to high school kids. So, I decided to go back to the classroom, and to understand my idiosyncratic journey, the timeline is crucial:

I began teaching in 1998, before the passage of No Child Left Behind and the onset of intensive training in teaching to standardized tests. In fact, I hardly got any training at teaching literature at all: Mostly, I took a methods class from a college professors, and in my practicum and student teaching experiences, my mentors mostly said, “Here’s how to assess writing, and the content of these novels is up to you.”

When I left teaching for law school in 2004, I was just beginning to get trained in Standardized Tests. But, truth be told, I was much more influenced by my critical thinking skills training in Gifted Education, along with a love for movies when I reviewed movies for an early online magazine.

I went back into the classroom in 2009, right after the Great Recession financial system crash. Long story short, I ended up in a private college preparatory academy with a bent towards the liberal arts—where we explicitly did not teach to high-stakes standardized tests. That was part of the point of private school: the Standardized Testing Regime and “Accountability” are for, you know, kids in those schools. No need for that here. Literally, never once in my twelve years in private school did I encounter anything like the State Standards that are the basis for your existence in public school.

I taught sophomores in a kind-of “Pre-AP” class, but mostly, I was left alone to develop my practice however I wanted, while my friends and colleagues in public schools were grinding through “text-based passages” and the like. So, because I worked outside the system for twelve years, I developed a Critical Thinking Skills curriculum that reimagined and, humbly, rewrote Bloom’s Taxonomy into a scaffold to build rigor into my course. And, armed with my training in Constitutional Law, started developing a methodology for teaching literature while, again, my friends and colleagues were shackled by the Standardized Testing Regime.

That’s where Living Literature comes from. Now I’ve moved back into working with public schools, and, being a small town kid, this is my truer self. This project is an attempt to bring some of what I learned outside the system inside the system, especially at a time when our nation’s History and Literature teachers are facing literal death threats for simply doing their jobs.

Statue of James Woods Green (1922), First Dean of the University of Kansas School of Law, From Which I Graduated in 2007, Here Memorialized on Mount Oread For All Jayhawks From Here to Eternity, Pontificating Some Pretentious Nonsense to This Knee-Breeches Lad About the Majesty of the Law or Whatever.

Part 2. Why We Teach Literature Like This: Modernism and the Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution’s Logical Outcome Was Standardized Tests

When I returned to the classroom and started preparing students for AP exams, I began studying the history of education itself: Basically, how did this become the way we teach literature? Why do they ask us to divorce literature from its historical and cultural context, except to the extent that we need to understand snippets, passages, and the “author’s purpose”?

As with a Legal Education, Advanced Placement and other standardized testing regimes are based in scientific thinking that evolved from the Enlightenment.

In short, the mission is to make the study of Humanities objective. Just like the law is nothing more than a battle between competing rational analyses.

To oversimplify, Modernist thinking (I will use this term in the T.S. Eliot sense, explained here) attempts to “scientificalize” all disciplines into methods of finding the single “correct” answer. This is the grandchild of the 18th and 19th modes of thinking that led to the Scientific Enlightenment (itself a grandchild of Copernicus, Newton, etc.), which gave us the first science labs, the scientific method, and new scientific disciplines. This is when, for example, curious and enterprising professors and students (and “hobbyists”) created the practice of Anatomy. This involved, among other methods, digging up recently dead bodies were from graveyards in the middle of the night in the London suburbs, taken to “operating theatres,” and pumped with electricity to be reanimated in an effort to discover the origins of life.

So, what does this have to do with teaching literature in the 21st Century?

Everything, as it turns out.

Literature and philosophy had been at the center of a traditional liberal arts curriculum, where moral inquiry was the primary purpose of higher education. You read the Western canon of great writers and thinkers to understand how to live the purposeful life: Socrates, Plato, Homer, Augustine, Shakespeare, Dante, Milton, and other dead white guys. A Socratic Seminar might pose the question, what’s the point of digging up these bodies and pumping them full of electricity to discover the origins of life? Should we be doing this? What are the moral hazards of unleashing a technology into the world without fully understanding the potential consequences?

The Author’s Picture of the The Old Operating Theatre Museum and Herb Garret in London, The Last Remaining Operating Theatre Where They Attempted to Reanimate Corpses With Electricity. Also, It Should Be Federal Law that Frankenstein Be Taught as the Foundational Text for Every STEM Program in the Country.

By the early 1900s, this mode of inquiry didn’t really fit the Modernist influences that transformed academia. Scientific inquiry taught us to search for objective truths using evidence and reason. Philosophical inquiry was too soft and squishy and “subjective” for the modern world. It doesn’t provide answers; it mostly just leads to more questions.

So, how do you teach literature in a world in which intelligence is measured by your ability to find the “reason”-based single objective answer?

Solve For the Author’s Purpose.

The Modernist movement imported scientific-type methods into interpreting literature, called “New Criticism.” New Critics tried to answer the question: What’s the “correct” interpretation of a text?

Because there can only be one, objective answer, there’s only one way to deduce the answer:

Reasoning Yourself To The Author’s Intent!

Solving For X: The Scientificalization of Literature

The most prominent example is T.S. Eliot, who was the Modernist literary critic (and prominent anti-Semite, which we will discover later, is not unrelated) in addition to poet and playwright. Eliot’s essay “Hamlet and His Problems” perfectly exemplifies this mode of thought: According to Eliot, Hamlet fails as a work of art because Shakespeare never makes clear exactly what’s wrong with Hamlet!

Hamlet is so elusive and confusing and slippery–so open to interpretation–because Shakespeare himself must have been confused. Obviously, based on the text, Shakespeare never really worked out what Hamlet’s problem is. So, Hamlet fails not because Hamlet can’t figure out what’s wrong with him–but that the author Shakespeare never explicitly tells us, the readers, what’s wrong with him.

Obviously, Both Shakespeare and Sir Laurence Olivier Would Fail AP Lit Because They Didn’t Explicitly Articulate a Concise Thesis That Clearly States Prince Hamlet’s Dominant Emotion.

Why is this a problem and make the play fail? Because, according to New Criticism, the only legitimate way to interpret literature is to find the author’s intent. You use the tools of literary criticism to decode the text, and that’s your answer. It’s literary interpretation as algebra, as if you’re interpreting the text in the same way you isolate X when factoring equations. You can’t use historical context, author’s biography, critical lenses, human virtues–-none of that, no more than you would use “historical context” to solve a quadratic equation.

Eliot calls this the “Objective Correlative,” which, in the very phrase itself, distills the “scientific,” “reason-based,” objective mode of Modernist thought. In his Hamlet essay, Eliot defines the objective correlative as “a set of objects, a situation, a chain of events which shall be the formula of that particular emotion.”

Right there in the definition he tells us that literature should be a “formula,” the algebra-fication of values and humanity that are articulated by art.

Now you can see the endpoint of this mode of Modernist thinking: teaching literature with Standardized Tests.

Standardized tests have to be…standardized. It’s very hard to standardize tests around the values-based inquiry of liberal arts because there’s many possible answers, open widely for debate. In fact, the debate is mostly the point.

That won’t do for standardized tests. There can be no debate over the algebraically-derived, single correct answer, which you must objectively arrive at based on specific rules of interpretation that are the logical outcome of reason. After all, the point of standardized tests is to measure your intelligence, and how can we know if you’re really smart if you don’t know how to solve for the objective answer? All this subjectivity stuff isn’t rigorous.

T.S. Eliot When You Develop Your Own Interpretation of Hamlet.

So, if the only way to interpret literature is “finding the author’s purpose”, that gives you X, and X is what we need if we’re going to standardize these tests. You think your own individual assessment matters?

Now you see why we teach literature like we do. Especially because the rise of high stakes standardized testing puts our jobs on the line, we teach Modernist, New Criticism, solve-for-X style literary analysis. Small passages, completely divorced from context, put in front of kids like little chemical equations to balance. And bigger questions about the novel as a whole are, mostly, expressed as “What did the author intend?” broad questions.

This is why it’s often awkward for literature teachers to try to “make the book relevant for our students.” It cuts against the way our study guides are designed, our assessments are constructed, the whole approach that’s been ingrained in us–with little or no explanation for why we teach like this. Especially now, when AP is nearly ubiquitous for most college bound students.

Trying to Figure Out How to MAKE THE LITERATURE RELEVANT FOR YOUR STUDENTS When Your Job Relies On Them Answering “Author’s Intent” Standardized Test Questions.

Part 3. Towards a New Methodology: Adapting Living Constitutionalism to Teaching Literature

Ok, so now, let’s return to Constitutional Law, the practice of law that’s closest to Humanities. Long story short, for my dissertation, part of my Conceptual Underpinning was based in Justice Stephen Breyer’s “Active Liberty” concept, so I had to read a bunch of really boring Legal Theory books about all this. But, this training seeped its way into my teaching, and my practice really did change as I intentionally began to apply these interpretative methods into my own reading of Literature.

Ok class, here we go: The dominant modes of Constitutional interpretation are, oversimplified, Originalism and Living Constitutionalism.

Originalism: How Conservatives Fix Meaning in the Past

Originalism is the idea that the Constitution means whatever the Founding Fathers intended when it was drafted. This school of thought was popularized by, and made dominant by, Antonin Scalia. There’s tons of writing on how unpersuasive, if not outright dishonest, this methodology is, so I will shorthand my view here:

There are different strands of Originalism. On the Supreme Court, for example, there’s Neil Gorsuch, a Textualist Originalist who believes that the only legitimate way to interpret the Constitution is by decoding the words themselves. As such, Gorsuch literally cites the Merriam Webster dictionary in his opinions. In his concurrence in Students For Fair Admissions v. Harvard (2023), he understands “discrimination” in Title VI of the Civil Rights Act by looking at a Merriam Webster dictionary from 1964, and then decodes the rest of the phrase with further dictionary definitions.

However, most Originalists think they function like historians, but, truth be told, without the complexity of actual historians. In reality, students who are really good at DBQs on the AP Test (Document-Based Questions, where students synthesize their analysis of various primary and secondary sources to answer a question) are engaged in more rigorous thinking than most Originalists. Their opinions are composed as if they’re taking us back to 1793 in a time machine, definitively showing us the objective, inarguable truth of what the Founders intended.

But unlike real historians, Originalists seek simple, definitive answers, rather than grappling with ambiguity and complexity. Rarely do Originalists offer competing interpretations based on what words meant in context, or explain the fierce disagreements about the interpretation of Constitutional passages at the time they were written. Typically, the Originalist tone is that, if you can’t plainly state the Founders’ intent, you’re simply not being rigorous enough to understand that What The Founders Meant. You’re imposing your politics on the inviolable words of the Founders.

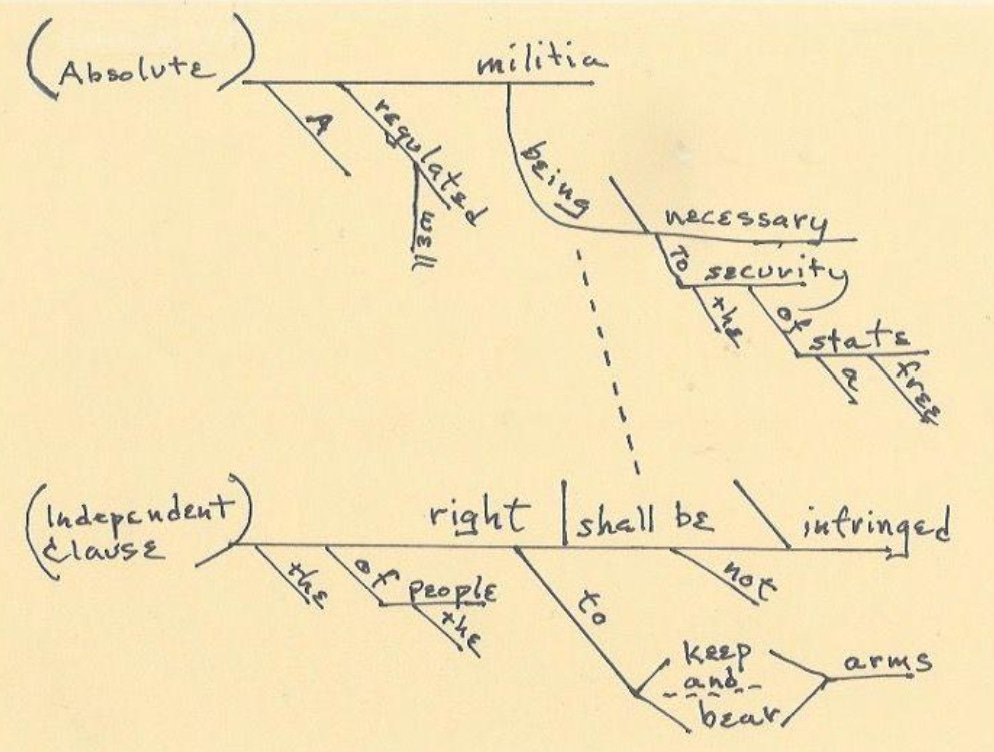

So, if you’re an actual historian or humanities scholar and say, no, look, you can’t definitively say what Thomas Jefferson might have thought about the Constitutionality of AR-15s, they will say: Nope, cite some contemporary Federalist Papers, and perhaps do some sentence diagramming.

A For-Real Diagram of Justice Scalia’s Grammatical Interpretation That Was, Yes, Actually This Detailed in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), Which Established for the First Time in the Republic’s 200+ Year History an Individual Right to Bear Arms.

In this way, the Originalist Constitution was written on stone tablets, like Moses receiving the Ten Commandments from Mount Sinai, and the justices’ methodology is to bring that meaning down the mountain to us lay people below. The Founding Fathers not only are sacred, their word is LAW.

This is, basically, author’s purpose style interpretation. Modernists use the same tools and modes of inquiry, locking meaning in the past. This is why Conservatives, who seek to conserve institutions and ways of thinking in the past because they are enduring truths, generally think along these lines. The truth lies in the past, which is what it should be today and on into the future.

Conservative Legal Theory, Abridged.

Living Constitutionalism: How Progressives Evolve Meaning into the Present

The “Living” Constitutionalists tend to be political progressives. To them, our notions of morality and ethics and rights and “they way things ought to be” evolve and adapt over time. Still, there are principles and values that endure and can be applied to the past, present, and future, which are the foundation for our judgments.

But to understand the literature of the past, context is important: When reading Antigone, what was happening in 441 BC Greece helps us understand why the Athenian priest Sophocles wrote the Theban Trilogy as a crisis of faith in the gods. And then we bring those ancient truths and understanding through time up to the present—bringing the moral questions of Antigone to bear on the corpse of Michael Brown lying in the streets in Ferguson, St. Louis County, Missouri.

We ask ourselves, how is today like it was then? How is it different? How does this help us understand what we should think about today? What can the unnerving sight of an unburied corpse tell us about the power relationships in a society?

Theater of War in Brooklyn Imagined Antigone in the Suburbs of St. Louis, Creating a Communal Experience Not Unlike the Catharsis of the Greek Theater. They Eventually Brought This Religious Experience to My Home State Here in Missouri.

Living Literature’s Guiding Light: Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson

The name "Living Literature" is inspired by Justice Stephen Breyer's "Living Constitution" theory, in which the Constitution is a document that evolves and adapts to its current environment like a living organism. The objective isn’t to banish “author’s purpose” and textualist style analysis from teaching, but to use it as simply one tool in a larger toolkit of interpretation–often, the beginning point.

This mode of Constitutional interpretation is the intellectual project of Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, who actually rejects the term “Living Constitutionalist” for her writing. She claims to be an Originalist, reclaiming that word from the conservatives who seek to return the law to the time of the slaver Founding Fathers.

She claims “Originalism” because her extraordinary opinions trace the law from its founding to today, in an intellectually rigorous and wide-ranging pursuit of meaning that brings the wisdom (and shortcomings) of ancient documents into the modern world.

In my view, no matter which label Justice Jackson chooses, what she really does is explain how an ancient document from a very different time, under a very different context, can and should still have relevant meaning today. Its enduring principles are fixed at the time of writing, and the path forward is grounded in those values, interpreted in factual, historical context. This is how a fixed document can still govern a union that seeks to be “more perfect” than it was in 1793. We have to understand its founding principles as in constant tension and evolution to be able to survive. This is the only way to make a democratic republic endure.

Even if, I imagine, that Justice Jackson would reject the title, Living Literature is going to attempt to do for Great Books what KBJ is doing for the Equal Protection Clause of 1868. And in doing so, we will try to give teachers a framework for approaching literature in the classroom that gives students the tools they need to think through the extraordinary challenges facing their generation today. In a future post, I’ll take Justice Breyer’s framework, season it with Justice Jackson’s methodology, and adapt it to a literature context.

No, This Is Not a Stretch: Justice Jackson Has Said That Musical Theater Has Influenced the Way She Thinks About History and Law, and She Has the Pipes for Broadway

Part 4. Teaching Literature To Create the Skills for Democracy

Freed From Standardized Testing, Literature is the Most Rigorous Discipline

The Living Literature project is animated by this idea: Studying literature is the truest way to understand society. To enlarge our sensibility, to understand why people feel and act the way they do. Reading literature is the practice of understanding the humans telling the story–not just the author, but the characters who leave the author’s control once the book is out in the world.

The reason why Humanities used to sit at the center of university curriculum is because, to understand literature, you have to understand how all the other disciplines bear on the actual human experience of people in a particular time and place. Humanities was the hub; every other discipline was the spokes.

In this conception, studying literature wasn’t a particular skill revolving around the parsing of text through literary devices—the study of literature is really about understanding how the social history of a place creates the conditions of the plot, how economics creates the conditions of the characters, how the understandings of the physical universe of the time influence the perceptions of the characters, how the geography of a place influences the relationships between people….and on and on, you get the point:

To really understand a work of literature in full, you need to be at least versed in all the disciplines of the academy, and a master of some beyond simply knowing what a synecdoche is or how the Petrarchan rhyme scheme is different from iambic pentameter.

Once we understand that, studying literature isn’t like, just your opinion, man. It’s the most rigorous of all the disciplines.

Robert William Buss, Dickens’ Dream (1875). This Kind of Knowledge Requires Curiosity About Everything.

Democracy Only Works When People Can Understand Others

But beyond academic concerns of intellectual rigor, studying literature requires you to develop empathy. It’s not the only empathetic discipline of course–but that’s what the Humanities is literally about, it’s right there in the name.

Even the AP Test helps you do this. The first thing you learn in AP Lit prep is how to identify the narrator. Who is this person talking to me? Of course, they’re a construct of the author, but the perspective is rooted in time and place, and you have to figure out why they see the world as they do. That requires you getting inside their head, in the same way the author has created this fictional head space that you inhabit when you read.

Not only do you have to understand how history, economics, language, science, and all the rest bear on their worldview, but you have to understand their personal circumstances–you have to understand relationships, motivations–those things that make us human. This sometimes involves psychological theory, like with the Freudians, but really, it simply requires you to bring your own human experience to the story. For comparison or contrast, we are all bound together by the experience of having a difficult family, unrequited love, complex siblings–you know, life stuff.

Once we put all of this together, what is the life, work, personal, and professional skill you’ve developed?

Empathy.

Done well, thinking deeply about literature develops the brain muscles to help you understand where other people are coming from. Why do they think that way? Why did they do that? What’s going on with them? The more you study literature, the more reflexively you can answer these questions.

Seriously, in what walk of life would the ability to synthesize all this information into a reasonable range of possibilities for why people feel and act the way they act–where would this not be valued above technical proficiency? Where wouldn’t this be a tangible, concrete, definable skillset out in the real world that employers pay top dollar for?

Beyond employable skills, the ability to empathize–to analyze the historical record and bring those values into the present, while really listening to your fellow citizens to figure out how to live together in this nation:

This is the foundational skill of democracy. It’s not STEM or the “employable skills” or the “market value assets.” It’s the skills developed through analytical history and literary interpretation. This is what matters most in our current moment.

This points to the inherent….irony?...contradiction?...tension?...of education in a democracy:

State-sanctioned independence.

In a democracy, education is the empowerment of the young to topple their elders and make something new. Truly wise elders have the humility to understand that our fate is to become the villain that the youth fight against to regenerate a democratic society. Truly wise elders do not cling to power until they die: They understand that you allow yourself to become the butt of the joke, and then enjoy watching the youth create The Next Thing.

For real, this is the purpose of education in a democracy (body-shaming aside.)

The Only Movie Teacher Who Understands the Democratic Mission of Education: Dewey Finn (Mr. Schneebly) Who Told The Kids That If You Wanna Rock You Gotta Break The Rules, You Gotta Get Mad at The Man, And Right Now, I’m the Man. Is Everybody Nice and Pissed Off? Now It’s Time to Write a Rock Song (Or Amend the Constitution)!

Who Controls the Past Controls the Present

If you don’t believe this, ask yourself: What is the epicenter of our current politically-charged culture war over schools? That’s right, it’s history and literature. Because those are always the most important components of education, no matter what the “jobs of the future” and “learn to code!” people tell you is the purpose of school. In the end, it always comes down to history and literature because these stories from the past are used to decide the present. Political actors understand that who controls the teaching of history and literature are who gets the first crack at teaching young people Why Things Are Like They Are.

This is why the 1987 English Coalition Conference, the largest and widest ranging summit of English teachers from elementary through college, themed their conference “Democracy Through Language.” The whole point, from Pre-K readers through PhD literary studies, is to teach citizens of a democracy how to understand each other so that we can negotiate how to live together in a nation. The National Council for the Social Studies also sees their mission as preparing citizens for democracy, and today articulates their purpose as quite literally “Safeguarding the Republic.”

These are the stakes, and truth be told, it’s the main reason authoritarian movements ban books, jail teachers, call us “groomers,” make our jobs so impossible that you quit, and defund history and the humanities: This creates the information vacuum they fill with their own propaganda, their own stories that justify why we should hate The Other, because they’re not us.

Part 5. This Really Is About Fighting Fascism: The Modernist Roots of Standardized Testing

Fascism is a Modernist movement whose methods for interpreting literature are the basis for remaking society in the image of the dictator. Standardized testing is rooted in the same racist and eugenicist ideas of Fascists. Seriously, the explicitly racist and eugenicist history of Advanced Placement, the SAT, and the rest of what would become the high stakes standardized testing regime is all right there. This is not an accident: The Fascists themselves developed and used these methods to further Fascism.

Mussolini and Hitler in Rome, 1943. If You Don’t Pass Their Tests, They Put You on a Train.

There’s a lot to all this, and if you want to deep dive into it, I cannot recommend more highly Roger Griffin’s Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning Under Mussolini and Hitler. Here, Griffin confronts historians who turned a blind-eye to the relationship between Modernism and Fascism by reducing their understanding of Modernism to merely aesthetics: “This architecture looks like modernism” or “This poem has modernist elements.” Griffith says this aesthetic is part of the whole point, which tries to construct a world that has collapsed into disorganized rubble and is being rebuilt by a Great Man. No wonder Mussolini and Hitler loved it.

This brief review by Marla Stone is a great summary of Griffin’s work connecting Modernism to Fascism. Basically, Griffin takes Modernist literary theory, art history, architecture, etc., and then imposes it onto the intellectual and political theories of Fascism. This shows how Fascists and Nazis not only adopted Modernist style to create propaganda, but used the “scientific” intellectual theory of Modernism to create a “one true answer” politics.

That one true answer? The Dictator.

That’s how Fascists “mobilized cultural and political modernism is the name of ‘the Nation’ and ‘the Race.’”

Remember early when I said that the most prominent Modernist poet was the antisemite T.S. Eliot? That’s not an accident.

Here’s how that intellectual project works:

Modernist literary theory–the theory we use to justify standardized test based education–says that there’s only one true answer. The job for the writer and reader is to reduce the interpretation to X.

So, if you’re an angry young German in the 1920s looking at your country’s physical devastation and economic degradation after World War I, you want an answer for why this happened and why your country sent you off to be probably be slaughtered in the trenches. Perhaps you could try to understand What Happened by tracing this back a century or so to the ongoing struggles between the Enlightenment-based French Republic and the Militarism-based Prussian Empire, and how the Fall of the Bastille gave rise to Napoleon’s conquests of Eastern Europe, triggering the slow-motion collapse of European Feudalism, eventually leading to the Second Empire of Napoleon III and the Franco-Prussian War, which ended with Otto von Bismarck signing a treaty in the Hall of Mirrors in the Palace of Versailles establishing the German Empire, because that room had paintings glorifying the French conquest of German lands under Napoleon, and so that’s where France eventually humiliated Germany after World War I, making them sign the Treaty of Versailles on the Hall of Mirrors.

Now ask yourself, why did all this happen and what does it mean for rebuilding Germany in the wake of our great defeat? Are these punitive, society-destroying peace treaties just the expression of nationalistic chauvinism, and perhaps the way to break this cycle is through rebuilding and rehabilitation?

Or, you might want a simpler answer. Obviously, since our great nation cannot be at fault. There had to be some shadowy, state-less people who aren’t quite, you know, one of us, even though they live among us. They secretly control everything: the banks, the media, the universities—all of it.

Solve for X = The Jews. They’re to blame for everything.

So, to make our great nation great again, we need to isolate that pernicious variable in our national formula. And eliminate that variable.

You can hear this mode of thinking in Nazi’s own words: The Final Solution to the Jewish Question.

The Treaty of Versailles by Joseph Finnemore (1919). We Can Ask Hard Historical Questions About How We Got Here, Or We Can Just Blame The Jews.

It shouldn’t be surprising that Fascists, Nazis, Stalinists, and other authoritarians love this mode of Modernist thinking. It trains people to think how the dictator needs you to think: Very clear and simple story, one definitive answer based on what the author tells you the answer is. What is the Law? Whatever the “author”itarian says it is!

This is also why 20th and 21st century authoritarian movements love technology and science and “data.” Modernism gives them a way to “scientificalize” their bigotry in “evidence” and “reason.” I’m not a racist, I’m just looking at all this data objectively, so it’s not me who is saying that Black Americans are less intelligent than whites—that’s just what the evidence reveals as objective truth.

Technology and science and “data” are deployed to distance you from your own values that, on some level, you must know are evil. So, you use the language of STEM that’s “objective” and “rigorous,” making “moral inquiry” and “ethics” simply subjective, non-rigorous opinions unworthy of being elevated to the same intellectual plain as this “data-driven evidence” of Why Things Are Like This.

This is what Mark Twain meant when he wrote in his autobiography that “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics.” That’s how “respectable” bigots launder oppressive, dehumanizing ideas into respectable institutions of power, whether they wear robes in courtrooms or lab coats on university campuses or suits in the halls of Congress. They dress up gutter bigotry with Race Science charts and graphs. Literally, that’s what gave us The Bell Curve. It’s how the literal Nazis justified racism:

The Nuremberg Laws Codified This “Scientific” Chart of “Racial Ancestry” Into the Law to Decide Who was “Too Jewish” to be a German. (The Answer: Three Jewish Ancestors in the Direct Family Tree.)

That damage isn’t just inflicted by authoritarians; my friends and colleagues in the STEM-emphasis, vocation-oriented “school should only teach you how to get a job” movements have weakened democracy by convincing entire generations of Americans that teaching History and Humanities are “useless.” This is why nearly every policy discussion in education going back at least two generations must be “based in data.”

They have convinced educators and education policy makers that without data, what you’re advocating isn’t real or important: If you can’t measure it, we shouldn’t be teaching it. So it gets sequestered as an “unserious” part of school, bereft of funding, focus, and often, just basic respect from policymakers, parents, and your own colleagues in the “serious” subjects.

And worse, if you teach one of those useless subjects, you’re not really a professional. You’re less than actual professionals, like lawyers and doctors and architects and teachers of important subjects. Educators aren’t even close to the Second Best Job. Just imposing your opinions on students. Indoctrinating them!

You can’t think about teaching values-driven, moral and ethical inquiry in the Humanities. History should only teach “the facts,” which completely misunderstands what history actually is.

So, yes, I actually believe that the past two generations of Data-Driven Education Reformers are also responsible, in part, for the erosion of democracy. I actually believe that the extreme focus of money, time, and focus on STEM Education has had catastrophic consequences for the health of the nation, and made us collectively unable to confront the big questions of our era. And that Standardized Tests, in the way we give them today, prime people for authoritarian government.

Since A Nation At Risk was published in 1982, the subsequent reactionary Education Reform Movement has opened up a void in the national narrative where the techno-fascists in Silicon Valley and “Unitary Executive”-ists in the government can insert their preferred stories to justify their own authoritarianism.

When the kids say, “These tests are fascist,” they’re not wrong. The origin of the SAT is literally rooted in racism and eugenics from the 1920s.

Just know this: Winston Churchill was not confused about the value of History and Humanities (even though he probably didn’t say “History will be kind to me, for I intend to write it” and is likely responsible for the Bengal Famine).

Winston Churchill Reviewing His Notes Over a Scotch-and-Water as He Decides How Kind History Will Be to Him Because He Is Writing It (Photo by N. Farbman for Churchill’s The Gathering Storm, 1949).

Part 6: Living Literature Applied: Charles Dickens and A Tale of Two Cities

This idea that Literature Lives from the past into the present and on into the future is why one of our first books is going to be the one with the most famous opening line of them all: A Tale of Two Cities. We’ll figure out how it could be the best of times and the worst of times at the same time. Hint: Charles Dickens was a journalist who knew how to gin up outrage to sell subscriptions. He also understood that if you think you live in extraordinary times, well, gentle reader, We’ve Been Here Before.

When he wrote Cities in 1859, he understood his times as an extension of the French Revolution of 1789, and he was also famous enough to know that his words would have meaning in the future, whenever his readers picked up the book. In other words, Dickens would say that the times in 1789 were the same as they were for him in 1859 and are largely the same for us here in 2025.

So, if you’re looking for a way of thinking about our current moment beyond our current moment–with the perspective that the outrage of the day doesn’t really tell us that much about why things are happening, that we need to connect emotionally and psychologically with people who have been where we’re at—that’s what we’re going to do with A Tale of Two Cities.

The Wisdom Contained Herein Is Immeasurable.

(Not Really, You Can Teach Sustained Critical Reading and Critical Writing Skills Within a Values-Based Framework, Guided By Assessments that Accurately and Reliably Measure Student Competency in Deploying Higher Level Critical Thinking Skills. If You Care About Saving Democracy Rather Than Obsessing Over NAEP Scores.)

There’s a great passage right before Dickens describes the Storming of the Bastille. In the chapter “Echoing Footsteps,” The Manette family, French expats who fled Paris during the tyrannical reign of Louis the XVI, are living a comfortable life in north London, in the middle of a newly-built Georgian square, where row houses surround a lush garden in which families often share meals and spend time together outside.

The family and some of their friends are in the garden, when a great storm comes. They hear the footsteps of all the people running to their houses, and Lucy Manette hears the echoes of her heartbeat as they scatter. She feels the heartbeat of her little girl, 6 year old Lucie. Her heartbeat, the heartbeat of her daughter, and all the heartbeats of the running people are heard together through this common experience of the storm.

Dickens says, “But, there were other echoes, from a distance, that rumbled menacingly in the corner all through this space of time. And it was now, about little Lucie’s sixth birthday, that they began to have an awful sound, as of a great storm in France with a dreadful sea rising.

Soon after, Dickens cuts the narration to the poor neighborhood of Saint Antoine in Paris, where a mob of revolutionaries is gathering to storm the Bastille.

The echo is a beautiful, defining image for Dickens: And, considering that A Tale of Two Cities is a historical fiction, the echo is something like Dickens’ idea of history itself. An echo is a sound, made by something in the past that happened somewhere else, travelling through space and time to us in our present time and our present space, and then leaves us to be heard in the future by others elsewhere.

In other words, our common human experience is interconnected across time and space. Those footsteps headed toward the Bastille will eventually be heard in London, with catastrophic consequences for the Manettes. The end of the book is something like a present-tense prophecy, but also set in the past.

Whatever is happening to us now, it’s because of the things that happened in the past, and the course we choose now will echo into the future. Yes, we live in extraordinary times, but people have always lived in extraordinary times, and it's the literature of the past that can help us cope with the present and create a better future.

This, for me, is how literature lives, and it’s the guiding idea of this project.

The Author’s Picture of Bedford Square, Where He Surmises That Charles Dickens Set the “Wonderful Corner For Echoes” in A Tale of Two Cities. We Will Go There, Spiritually, During Season 1 of Living Literature.