A Christmas Carol, Stave I: Marley's Ghost

Ebenezer Made a Small Fortune with His Family-Less Loan Shark Business Partner, But Now Marley's Dead and Scrooge Must Endure Purgatory

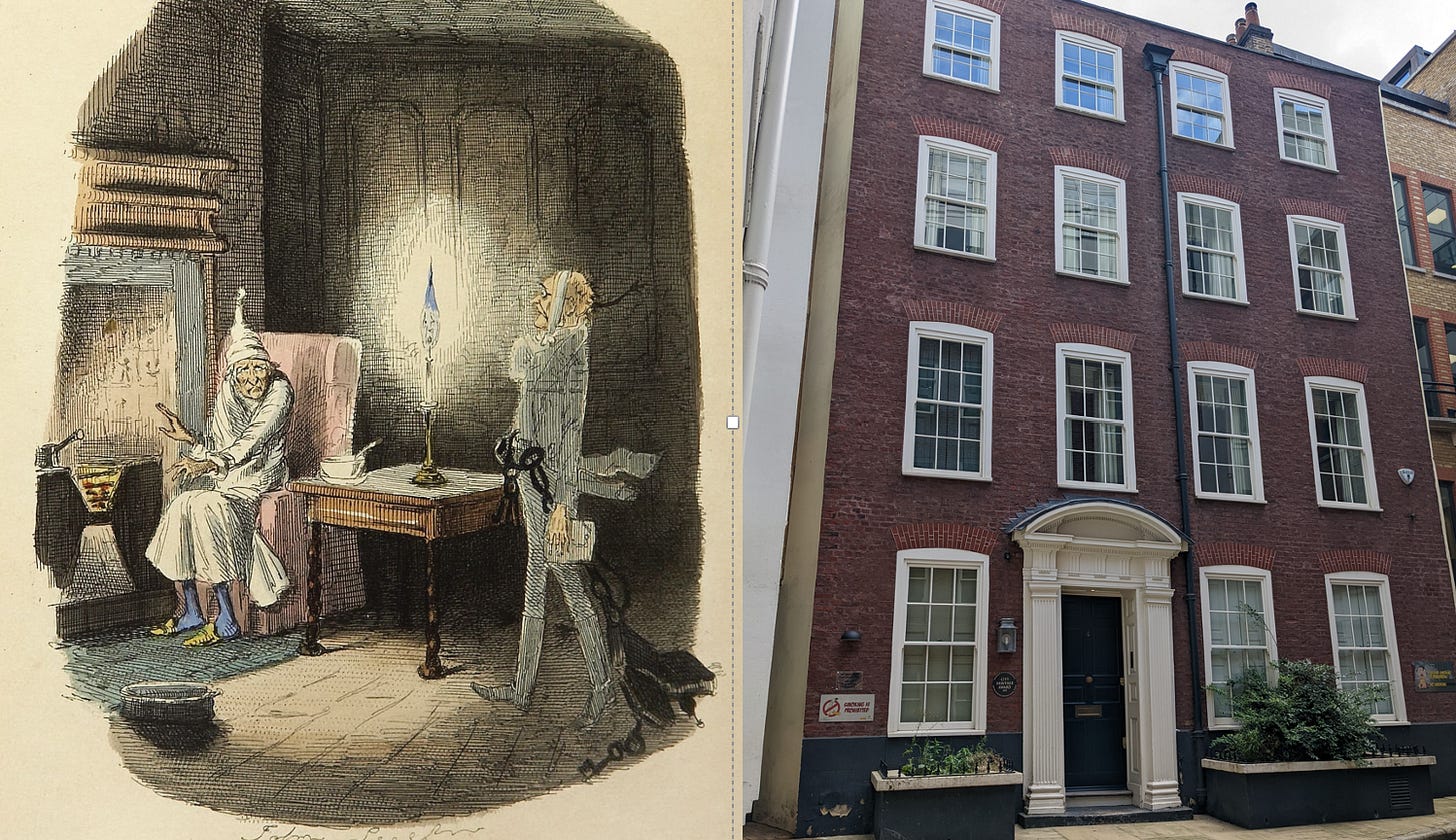

John Leech’s Illustration of Marley’s Ghost Confronting Ebenezer Scrooge for the Original 1843 Publication of A Christmas Carol. On the Right, the House that Richard Jones, London Tour Guide Specializing in Dickens, Identified as the Likely Model for the House Scrooge Inherited from Jacob Marley.

This guide will:

1) Provide a conceptual framework for understanding A Christmas Carol, and

2) Dig into the details to flesh out this deeper understanding.

My framework for A Christmas Carol is, admittedly, a bit speculative—but not without a factual basis. This framework helped me capture Dickens’ message and the mood:

Scrooge is in Purgatory.

Purgatory

In medieval Christian and later Catholic belief, Purgatory is an intermediate after-life space where souls are purified before entering heaven. Purgatory doesn’t exist in most Protestant beliefs systems: Martin Luther called Purgatory “unbiblical” and, more or less, a way for corrupt Catholic priests to sell indulgences. In Lutheranism, there is a scripture-based “in-between” space called “Hades,” but it’s not where sins are purged from the soul.

Over time, Dante’s vision of Purgatory came to define the idea, especially after Michaelangelo virtually canonized The Divine Comedy by including scenes in the Sistine Chapel. The Divine Comedy isn’t just Dante’s Inferno–the Inferno is just Part I, where Virgil guides Dante through the circles of Hell. Purgatorio is Part II, where Virgil (and, later, Dante’s muse Beatrice) guides Dante through the Terraces of Purgatory, where souls are bound for a certain time to do a certain punishment, the length of which is determined by the severity of their sin and the sinner’s level of contrition.

Conceptually, Purgatory is very different from Heaven and Hell. In Dante’s vision, Inferno and Paradiso are eternal punishments or rewards, so there is no passage of time. Purgatory, however, is time-bound—part of the purification is feeling the passage of time. Purgatory is also a physical imprisonment, confined to the Seven Terraces of Purgatory.

Why seven terraces?

Because souls in Purgatory committed one of the seven deadly sins, which betrayed true love in your time on Earth. You do your punishment in Purgatory, cleansing your soul of Wrath, Envy, Pride, Sloth, Lust, Gluttony, or Greed, and you emerge from the Terraces at the top of the mountain ready to enter Paradise.

Perhaps because I’ve taught both A Christmas Carol and The Divine Comedy, Dante’s influence on Dickens seems obvious: A Christmas Carol, like The Divine Comedy, is a story in a condensed time frame where a sinner is guided by a ghostly figure in a tri-partite structure to deeply interrogate the nature of sin and the true meaning of Christianity.

However, the only scholar I’ve found who has written on this is Professor Stephen Bertman at the University of Windsor in a 2007 article “Dante’s Role in the Genesis of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol” from Dickens Quarterly in 2007.

Professor Bertman deep-dives into evidence of Dickens’ knowledge of Dante, that certain books were found in Dickens’ libraries at his homes–-but most intriguingly, we know that the most prevalent translation of The Divine Comedy in Dickens’ time was by Henry Francis Cary, an assistant librarian in the British Museum, when a “young Dickens was frequenting its reading room as a cub reporter intent on enlarging his mind.”

There’s no proof of the two’s meeting, but considering the circumstances, it seems very likely that, even if they did not meet, Dickens would have been familiar with his work on Dante. Dickens was extremely well-read, and when you consider that:

Very specific lines from Scrooge are very similar to lines in The Divine Comedy,

The similarities in the physical descriptions of Satan and Scrooge, and

Dickens employs the same metaphorical structures to convey the same ideas about sin and punishment and redemption,

It’s very likely that Dante’s Purgatorio deeply influenced Dickens’ conception of A Christmas Carol.

Though Dickens was not a Catholic, he was also not a doctrinal Anglican, and was deeply influenced by canonical writers who worked in the Catholic tradition. Dickens was very aware of his own legacy, consciously trying to put himself on this top shelf of Legendary Writers. “A Muppet Christmas Carol” even makes this a joke!

So, look, if the best of all A Christmas Carol adaptations literally puts Dickens next to Dante, then we can too.

Narrator

In the Preface, C.D., as he signed his books, says,

“I have endeavoured in this Ghostly little book, to raise the Ghost of an Idea, which shall not put my readers out of humour with themselves, with each other, with the season, or with me. May it haunt their houses pleasantly, and no one wish to lay it.”

Here, Dickens establishes two things: First, this is a GHOST story, intended not to scare or scold, but to haunt pleasantly. So, dear reader, no matter how awful this first part is, all will be well in the end.

Second, it is I, your “faithful Friend and Servant,” one Charles Dickens, that will be your guide. This is important.

A Christmas Carol is written in something like “First Person Omniscient,” where he, Charles Dickens, is the narrator of the story.

This was not just a literary device, but an essential part of Brand Dickens. Dickens was deeply involved in the business of publishing, fighting with his publishers his entire career. So, Dickens built into his style an identity that was unique and portable across platforms. When you bought a subscription to his literary magazine, Dickens didn’t want you to experience a Chapman and Hall publication as much as he wanted you to feel like Charles Dickens is there, in your sitting room, sharing a story with you.

This personal connection was not just Dickens’ way of telling the story, but his way of building a relationship with his readers. Thus, his writer’s voice is much better understood as a script, which is why Dickens, who wrote before cinema, is still so adaptable. Indeed, later in life, Dickens made most of his money performing his own scripts based on his books–-almost like the literature was created for the performances. He basically invented the book tour, if not the very idea of the “lecture circuit,” and it was great business.

As a literary matter, if you find Dickens hard to slog through, you are not alone. Dickens is best enjoyed aloud, and that’s why A Christmas Carol works so well on the stage, where a Dickens stand-in, like Gonzo in A Muppet Christmas Carol, performs lines from the text. Dickens considered himself an actor, and he wrote for professional actors to perform. He published serially, where his works were read aloud in pubs and ale houses–-performed by the dockmen who could read and loved to ham it up.

Dickens’ omniscient narration is very important to his structure: Dickens’ stories jump from place to place, like a Baz Luhrmann film where the camera can be backstage at an opera houses, fly out of the window above the great city, and swoop down to find the man walking the outskirts of the city. Dickens very much wrote cinematically, with deeply descriptive visual passages, atmospherics that’s like hand-written cinematography, and a narration camera that–in this story, literally flies Scrooge across England to see the effects of poverty on the people.

Gonzo in “A Muppet Christmas Carol” and Charles Dickens, Photographed by Herbert Watkins in 1858. They Both Performed the Role of “Charles Dickens.”

The Opening

There’s a lot to cover on the first page because Dickens lays down a lot of context: He basically gives you the point of the story upfront, then starts the narrative. In his first paragraphs, Dickens often uses unusual punctuation that directs you to his point. Here, Dickens opens A Christmas Carol with:

“Marley was dead: To begin with.”

That colon: Is important. Dickens needs you to know that Marley is DEAD. This is a ghost story, it involves the supernatural, it is spiritual. Scrooge is not imagining Marley, there’s no dream-sequence literary prank here. Dickens wants to establish the religiosity of the story: Thus, Marley is dead as a doornail.

“Dead as a doornail” is a funny phrase that extends back to Shakespeare’s time. Nails used to be handmade and very sturdy, often repurposed from project to project over decades or even centuries. Door nails would hold together wood from both sides of a door, so the nail would be driven all the way through, bent near the tip, and then hammered into the door like a staple. Thus, the nail cannot be repurposed for another project, it doesn’t have another life. It is dead.

The history of “dead as a doornail” phrase sets up the joke in the second paragraph:

“The wisdom of the ancestors is in the simile; and my unhallowed hands shall not disturb it, or the country’s done for.”

Dickens often made this joke, that England is old and stodgy and traditional and dark, our practices don’t make sense, everything is inconvenient–-and if we change anything, the country will fall apart. This is Dickens expressing English conservatism, in the classic sense.

The third paragraph requires a bit of speculation. What was the relationship between Scrooge and Marley? Obviously, they were partners, and there really isn’t any hint of anything beyond that. We’ll see later, there’s some suggestion that Marley was older than Scrooge, and yet, the firm’s name was “Scrooge and Marley.”

Dickens does his most famous literary move, the long paragraph of Repetition. Here, Scrooge is the “Sole” to Marley: the sole executor (listed first), sole administrator, sole assign, sole residuary legatee, sole friend, and sole mourner. Marley had nobody else.

Is this why Scrooge sought him as a partner? Did he forge this partnership with an older man for the potential inheritance? We know that Marley also left Scrooge his house, which even in 1843, was valuable City of London real estate, as we’ll discuss. And, we will discover that Scrooge is very much afraid of debt. There’s very little else about the nature of the relationship, but it seems like Scrooge set himself up with a partnership for the money, as opposed to marrying Belle for love, who we will meet in Stave II.

The Author Taking You Into Newman’s Court, the Likely Location of Scrooge & Marley’s

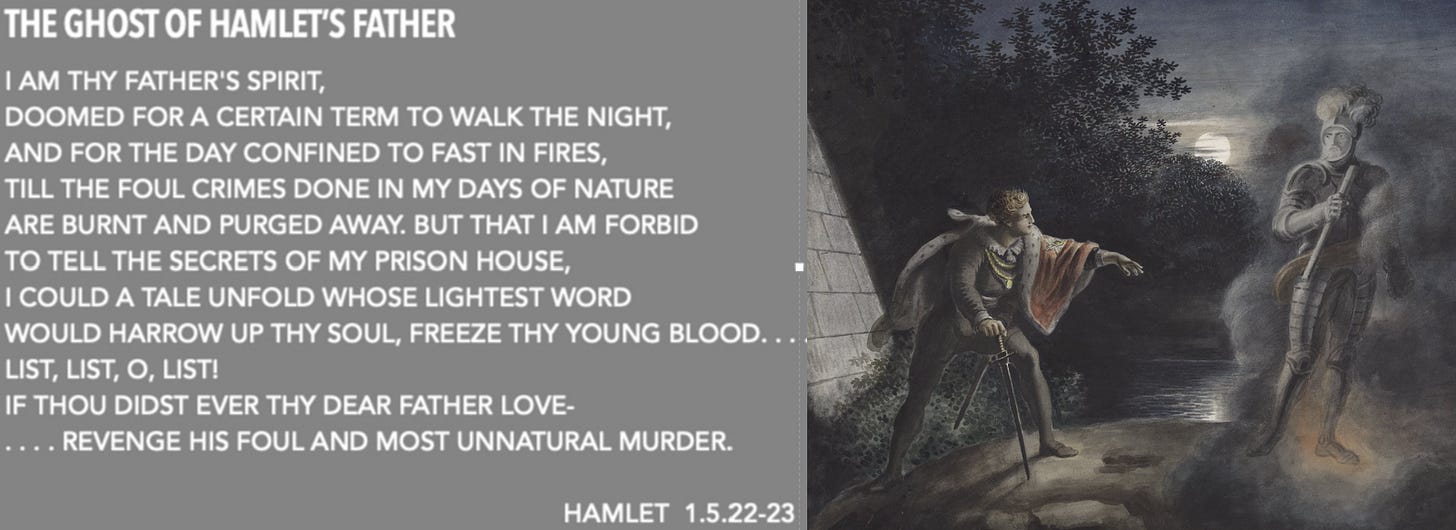

Allusion to Hamlet

In Dickens’ original handwritten manuscript, he crosses out a large part of the end of paragraph four. Declan Kiely, the former curator at the Morgan Library, which owns Dickens’ manuscript, writes in his introduction to the “Original Manuscript Edition” of A Christmas Carol that

“the ghost of Hamlet’s father is introduced, leading to a digression concerning the character of Hamlet that Dickens seems to have immediately recognized as superfluous and potentially distracting from the scenario he was establishing.”

I disagree. If we understand A Christmas Carol as influenced by Dante’s Purgatory, then the allusion to the ghost of Hamlet’s father makes perfect sense. In Hamlet, the ghost tells Hamlet that he is:

“Doomed for a certain term to walk the night, and for the day confined to fast in fires, till the foul crimes done in my days of nature are burnt and purged away. But that I am forbid to tell the secrets of my prison house, I could a tale unfold whose lightest word Would harrow up thy soul, freeze they young blood.”

That is…Purgatory: the spirit from beyond, warning of how sins in this world will doom you, for a certain term, to punishments until your crimes are purged and burned away.

Hamlet was written around 1600, toward the end of the reign of Elizabeth I. Her father Henry VIII separated England from the Catholic Church and created the protestant Church of England, whose tradition denies the existence of Purgatory. Shakespeare was writing in a time of doctrinal confusion: Are priests supposed to… not teach Purgatory now because the king wanted a divorce?

In the play, Prince Hamlet was sent to college in Wittenburg, the home of none other than Martin Luther, who tacked up his 95 theses eighty-three years before Shakespeare wrote Hamlet. Within Hamlet himself, part of his spiritual conflict is this very sudden change in doctrine: Prince Hamlet is being raised as a Protestant king, but he seems to have a Catholic soul: Not just his fixation on guilt, but his acceptance of the idea that his father’s spirit must be released from Purgatory.

Thematically, Dickens’ fiction fixates on guilt, forgiveness, and absolution–-as a writer, he is drawn to Catholic themes of Christianity much more than Protestant. In a Dickens novel, you have to make things right in this world to earn any sort of forgiveness. Nowhere does he suggest that the human act of baptism or the mere acceptance of God into your heart is any substitute for making wrongs right.

That’s why this allusion to Hamlet’s father opens the story: Dickens always worked towards Shakespeare’s reputation, so it makes sense that he would establish Marley’s ghost as something out of Shakespeare. Don’t take my word for it: Look again at Gonzo-Dickens on the shelf at Scrooge’s schoolhouse: The Muppets got this too.

The Ghost of Hamlet’s Father: Haunting His Son’s Soul to Earn His Way Out of Purgatory.

Scrooge is as Cold as Dante’s Satan

Next we get our first glimpse of Scrooge, a

“squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous old sinner.”

Sinner is the key word, which emphasizes Dickens’ set-up that this is, above all, a Christian story. Also notice how cold Scrooge is, not just in personality, where “no beggars implored him to bestow a trifle, no children asked him it was o’clock,” but how physically cold the “cold, bleak, biting weather” was.

This, again, is the influence of Dante: In Inferno, Satan isn’t engulfed by hellfire, but encased in ice up to his waist. Satan is cold, in the words of Dante scholar Rachel Jacoff, “the deepest isolation is to suffer separation from the source of all light and life and warmth.”

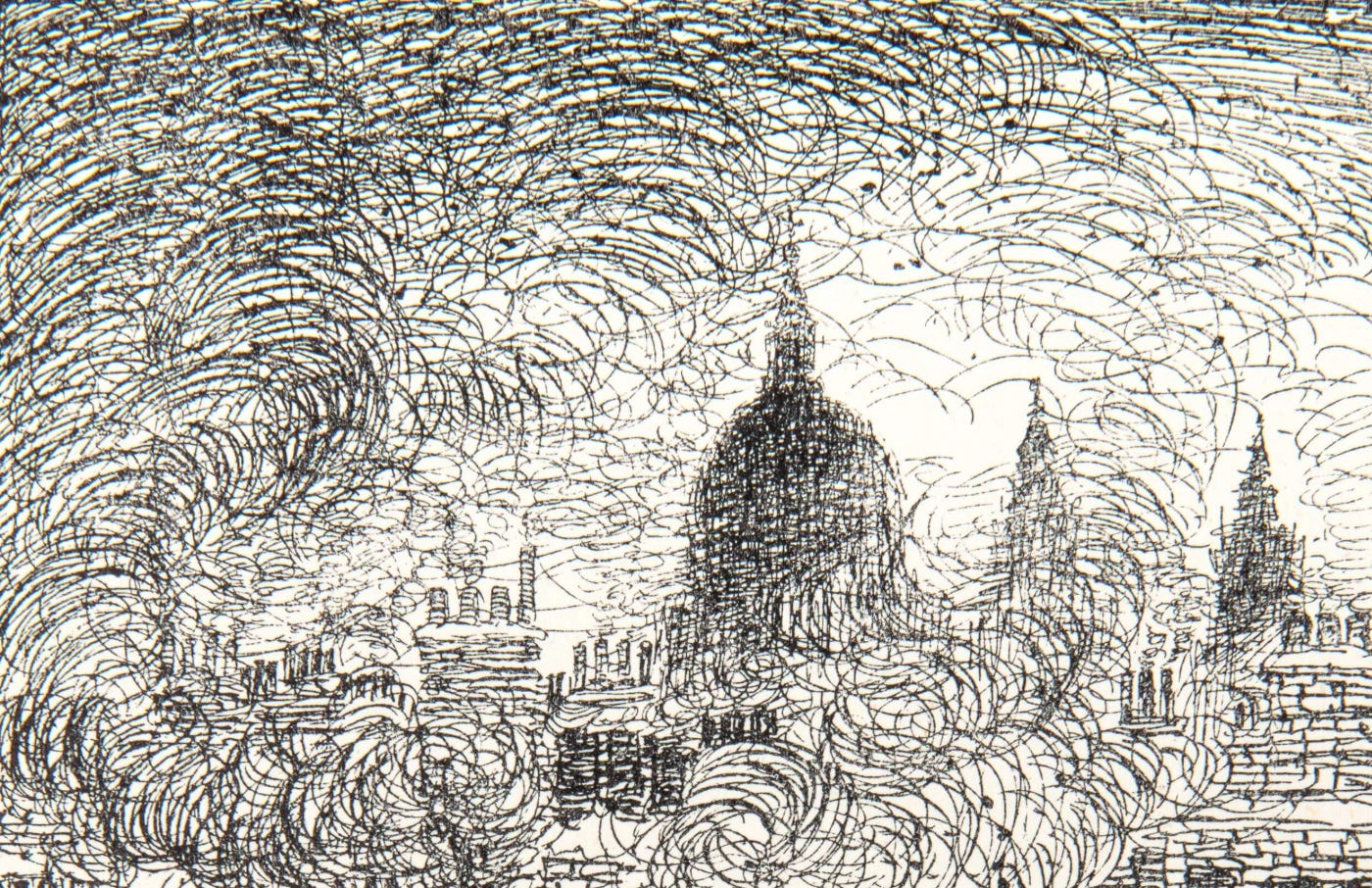

Think of every movie adaptation of A Christmas Carol you’ve ever seen: The tall buildings of the very center of the City of London shadowing out the sun, the fog settling into the narrow streets between the banks and counting houses, the small fires built in alleyways to provide small warmth, where this dark cloaked, shriveled man walks the urban streets with, in Dickens words:

“no eye at all, is better than evil eye, dark master!”

This is Scrooge, all alone in the empty Christmas Eve streets of London, towards the end of the Little Ice Age, when the Thames froze solid every year, until the pollution became so bad that it changed the composition of the water.

In this context, the “city clocks had only just gone three–it had not been light all day,” and

“the fog came pouring in at every chink and keyhole, and was so dense without, that although the court was of the narrowest the houses opposite were mere phantoms.”

With Dickens, the fog is always moral. In every Dickens story where the London fog sits on the city, expect the banality of evil. Not firebreathing revolutionaries, but the evil of lawyers, priests, schoolmasters, and moneylenders. Inside Scrooge’s office, the clerk’s fire had one coal–-much of the London fog of this time was smog, the constant burning of coal is how London became The Big Smoke. The smoke from a freezing fire is precisely an image from Dante.

This is not to say that Scrooge is Satan, exactly, but: He takes on one of the few jobs that the Bible namechecks as evil, a Moneylender. And, he commits one of the worst of deadly sins, Greed, that betrays his true love: Belle, his girlfriend who we’ll meet in the next Stave. Like Dante’s Satan, there’s nothing colder and darker than alienating yourself from love, and for Ebenezer Scrooge, that includes his family.

Arthur Rackham Illustration of Scrooge’s London from the 1915 Edition of A Christmas Carol.

Why Has Scrooge Alienated Himself From His Family?

In walks Scrooge’s nephew Fred, “A merry Christmas, uncle! God save you!” cried a cheery voice. In Stave II, we will learn that young Ebenezer was hated by his father, but his sister Fan convinced him to let Ebenezer come home for Christmas from boarding school, probably for good. But Fan also died giving birth to Fred…we will get to all of this in Stave II, but for now, it’s enough to know that Scrooge’s nephew just wants to connect with what little family he has, but doing so would force Ebenezer to confront his sadness and anger about the loss of his sister.

Bah Humbug!

This is when we get our first Bah! Humbug.”

Today, almost any use of “humbug” alludes to A Christmas Carol. But the word was prominent in the 1700s, even used as the verb “humbugging” to describe jokes and tall tales–there was even a play called The Humours of Humbug, featuring the character Harry Humbug. But over time, humbug became a political insult, describing “frauds on the public.” That new salt tax that they said wouldn’t raise the price of food? The people have been humbugged. The lawyer who charges you for unnecessary court proceedings? He humbugged you!

By the 1830s, humbug was applied widely to lying, deceitful politicians–especially Members of Parliament. Lord Kearsley’s speech about how much he cares for the poor? That’s humbug.

“Humbug” was in such common usage during Dickens’ time that his readers would have immediately grasped that Scrooge is saying to his nephew that Christmas is a fraud upon the public, and he wants no part of this dishonesty.

Which is why Scrooge tells his nephew, after his speech about the Christmas spirit, that

“I wonder you don’t go into Parliament.”

In the Dickens-verse, this is one of the worst insults you can levy. As a teenager, Dickens learned to write as a reporter for The Mirror of Parliament, which led to his lifelong belief that politics could never solve social problems.

To Scrooge, what else is humbug?

Marriage. When Scrooge asks him why he got married, his nephew says, “Because I fell in love.” For Ebenezer, that’s “the only thing in the world more ridiculous than a merry Christmas.” Again, this is why Scrooge is alone: He couldn’t commit to Belle, the reasons for which we’ll explore much more deeply in Stave II.

Scrooge’s Company

Now that we’ve spent some time inside Scrooge’s office, what, exactly, is his business? In the 1840s, Scrooge and Marley’s office in the Cornhill area of the City of London was home to several finance-related operations. A few blocks away sits The Bank of England and Mansion House, the real centers of power and wealth. We are about thirty years past the defeat of Napoleon, which elevated Britain to global supremacy. Thus, Dickens wrote Carol at the rise of the “British Century,” Pax Britannia’s control of the seas, nothing on the globe happened without the British touching it in one way or another.

It was here, in this tiny square mile of the City of London, where nearly all of world finance was moved. Right here in Scrooge’s London was where wealth was invested in the British Raj of India, the colonization of New Zealand and other islands in the Pacific, the occupation of Egypt to eventually build a canal that would halve the shipping time from the Far East, the “great game” of European domination waged against Russia, and the Scramble for Africa began.

It was also here where the wealth extracted from the people of those lands was laundered into the accounts of the British aristocracy and its investors. Literally, Scrooge’s London is also where Mr. George Banks worked, paying 17 Cherry Tree Lane and the services of his nanny Mary Poppins with plundered wealth invested in the Fidelity Fiduciary Bank.

However, Scrooge was not a banker on that scale. Rather, Scrooge seems to be a best-in-class, but still small time moneylender, perhaps the equivalent of a payday loan shark. This was during the time of the debtors’ prisons, where debt was criminalized and people of all classes could be incarcerated for owing private entities money.

As noted above, Dickens positions Scrooge as one of the worst sinners in the Bible: the usurious moneylender. The only time the Lord used the whip was to drive the moneylenders away from the Church.

Jesus Cleansing the Temple of Moneylenders. Not Unrelated: Scrooge McDuck.

Scrooge’s Politics

In his conversation with the men of charity, Scrooge reveals his politics, which Dickens draws from a specific source whose influence is still felt today. It’s unclear whether Scrooge’s contempt for the poor drove his choice of profession or vice-versa, but Scrooge’s contempt for the poor is core to his being:

“Are there no prisons? And the Union workhouses, are they still in operation? The Treadmill and the Poor Law are in full vigour then?”

The men of charity say, “People would rather die than go there.”

“If they would rather die, they had better do it, and decrease the surplus population”

This line is a direct quote from the works of English economist The Reverend Thomas Robert Malthus, whose work became known as the “Malthusian Trap”: The idea that increasing a nation’s food production would, eventually, lead to a decrease in living standards because the resulting population growth would lead to food shortages.

For Malthus, this created a spiritual problem: If population growth thwarts social progress, it’s imperative for a nation to impose standards of virtue on its people. Being poor and hungry must be the result of individual vice and wastefulness, not national policies or macroeconomics.

Not that Malthus didn’t have views on economic policies: He thought the Poor Laws created inflation, which hurt the virtuous well-off, and he supported the Corn Laws, which taxed grain imports and spiked the price of bread. If the poor died because they couldn’t afford food, well....

...they should have avoided all the vice and wastefulness that put them in this situation. And if that led to mass death, no need to let that sit on your conscience, they’re just the “surplus” population. Their own vice and wastefulness dictated their own fate, and they would be judged accordingly by God.

Malthus was controversial in his own lifetime. In “An Essay on the Principle of Population,” Malthus said that Rousseau’s views on income inequality and romantic individualism defied the mathematical logic that population increases exponentially while food supply only increases linearly.

Malthus also beefed with William Godwin, the utilitarian and anarchist philosopher who was married to early feminist Mary Wollstonecraft, whose daughter later became Mary Shelley, author of Frankenstein. Godwin was an early proponent of utilitarianism, but Malthus thought “the greatest happiness for the greatest number” would lead to famine.

This is the man that Dickens used as a model for Scrooge’s politics: The poor are poor because they lack virtue, and if they die, well, get on with it because the surplus population is taking food from the virtuous wealthy.

Thomas Robert Malthus, One of the Great Assholes of 19th Century Economic Thought, Whose Ghost Still Haunts Our Politics Today.

The City of London

After the men leave, Dickens shows us the scene outside, and in classic Dickens faction, “the fog and darkness thickened so, that people ran about with flaring links.” With Dickens the fog is always moral, and he makes clear that what’s about to happen to Scrooge isn’t just about his individual acts, but about his politics as well.

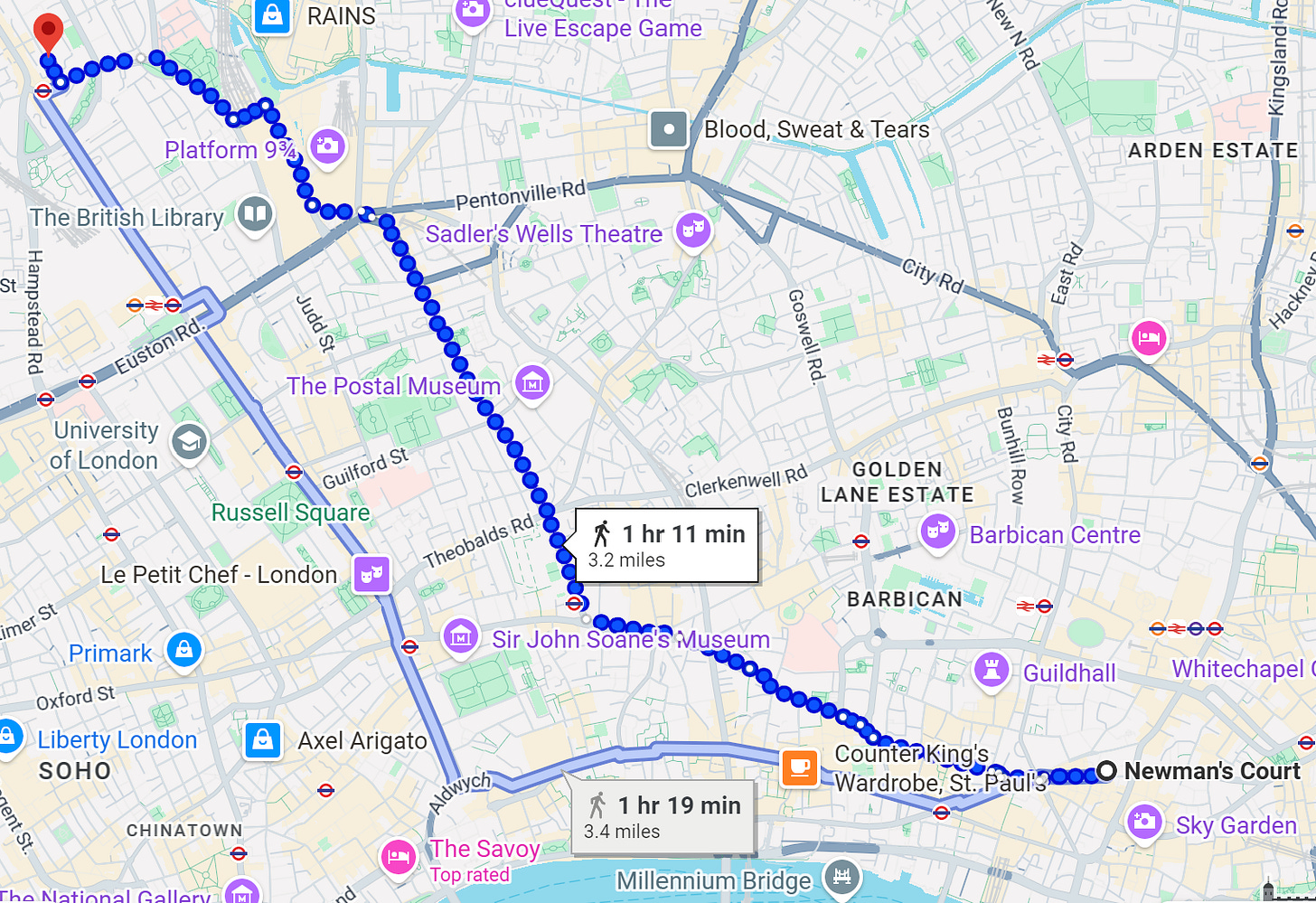

Here, Bob Cratchit asks for Christmas Day off, which Scrooge reluctantly relents to. When Bob leaves, he slides down Cornhill 20 times before walking home. Cornhill is an actual hill, a small hill, neighborhood just past Mansion House that Bob could have sled back in the day. But, and this is a detail that Dickens leaves out: Bob Cratchit’s walk home would take about one hour and thirty minutes.

The Cratchits live in Camden, a borough most known for its punk scene in the 70s and 80s. In the 1840s, though, it was a working class neighborhood far away from the city. Dickens himself lived there when he was little, during a time when his father was racked with debts. There’s a blue plaque commemorating Dickens’ residence there, which was almost surely the model for the Cratchit house.

Bob Cratchit’s Commute.

So, while Bob is setting off on his walk to play Blindman’s Bluff, Scrooge walks two minutes to the pub. Scrooge sees ragged men and boys warming their hands by the fire, he walks by the church, down a narrow alley that’s still there today, and you can imagine the frozen fog of A Christmas Carol settling into the alley before Scrooge takes his “melancholy dinner in his melancholy tavern.” This tavern, by the way, is still there: The George and Vulture, which hosts various Dickens groups for beers and dinners.

The Author’s Short Video Showing Scrooge’s Route to His Melancholy Tavern.

Marley’s House

After Scrooge takes his dinner, Dickens gives us some rather intriguing details about Scrooge’s deceased partner, Jacob Marley. Scrooge, apparently, inherited Marley’s house, which is tucked into a mews in the City of London. At the time, this would have been a very expensive piece of real estate.

This suggests that Marley had money, perhaps came from money, but had no family, or at least any that he would leave an inheritance. And yet, Scrooge’s name was first on the company door. The house is big enough that Scrooge leveraged the extra rooms to rent as office space. The basement was rented to a wine merchant to hold his casks. In Scrooge’s sitting room, Dickens details an old fireplace, “built by some Dutch merchant, long ago, and paved all round with quaint Dutch tiles, designed to illustrate the scriptures.”

The Dutch detail is key because it tells us that this house was once owned by a very rich merchant, perhaps from the Dutch East India Company from the Dutch Golden Age in the 1600s, when the Dutch Republic ruled the seas, dominating trade routes, the Atlantic slave trade, and extensive colonial ventures the world over. The stairwells were so wide you could get a hearse up it broadwise. Dickens is very much aware of the influence of empire on this space.

This is a serious piece of real estate. There’s even a disused bell “that hung in the room, and communicated for some purpose now forgotten with a chamber in the highest story of the building.” The bell would have been used to summon servants, but Scrooge, apparently, is too cheap to employ them, and so he takes his little saucepan of gruel alone, no one in this enormous house.

When Scrooge sees Marley’s face on his door knocker, Dickens says that Scrooge

“had not bestowed one thought on Marley since his last mention of his seven-years dead partner that afternoon.”

Whatever happened to Marley, it was traumatic, and Scrooge reacts to it the same way he reacted to the son of his dead sister: Shutting himself away from the world. Ebenezer Scrooge has suffered traumatic losses in his life, and for me, that changes the traditional perception of Scrooge as just plain old greedy:

He’s suffering from trauma—which the Ghost of Christmas Past, like some proto-Freudian spirit, will bring from Ebenezer’s repressed subconscious into his present world.

Marley’s Ghost

“Darkness is cheap, and Scrooge liked it.” Scrooge sits in his cheap darkness, “not a man to be frightened by echoes.” “Echoes” is one of Dickens’ favorite metaphors, often employed to suggest that the distant past is now finally catching up to you in the present. Thus, Marley’s Ghost finds his way through the heavy door to Scrooge, after double-locking himself in.

This is where we see more influence of Dante. Thus far, Dickens has described the City of London has a tiny, enclosed space encased in frozen fog, lighted only by small fires and gas lamps, in those hours on Christmas Eve when everything shuts down, as if we’re suspended in an alternative universe, and begin to really feel the passage of time before church, dinner, and gifts.

And so the ghost of Jacob Marley, body transparent, but otherwise dressed as he was in life–carrying a heavy chain made for

“cash-boxes, key, padlocks, ledgers, deeds, and heavy purses wrought in steel.”

In Inferno and Purgatorio, each sinner’s punishment is a metaphorical representation of the sin itself, so the punishment is a perverse re-enactment of that sin on loop. Murderers stand in a river of boiling blood, hypocrites wear robes that glitter on the outside but are weighted with lead underneath, that kind of thing.

That’s exactly what Dickens does with Jacob Marley: In life, a moneylender who burdened people with usurious loans, metaphorically chained to their debts; in death, he is burdened to carry the weight he once put on others, Marley’s chains made more heavy by the padlocked places where he held their money.

The ghost tells Scrooge:

“It is required of every man, that the spirit within him should walk abroad among his fellow-men, and travel far and wide. And if that spirit goes not forth in life it is condemned to do so, after death. It is doomed to wander through the world, oh woe is me!--and witness what it can no longer share, but might have shared on earth, and turned to Happiness.”

Notice the similarity to how the Ghost of Hamlet’s Father introduces himself:

I am thy father’s spirit,

Doomed for a certain term to walk the night

And for the day confined to fast in fires

Till the foul crimes done in my days of nature

Are burnt and purged away. But that I am forbid

To tell the secrets of my prison house,

I could a tale unfold whose lightest word

Would harrow up thy soul, freeze thy young blood,

The key phrase is “certain term.” In Hell and Heaven, the spirits do not feel the passage of time because the punishments and rewards are eternal. In Purgatory, however, the passage of time is part of the suffering that purges the soul of sin and prepares it for Paradise.

Shakespeare likely had not read Dante because The Divine Comedy had not yet been translated to English. Even though Shakespeare is clearly processing the Catholic / Protestant divide on Purgatory, there’s little evidence of The Divine Comedy’s use of metaphor to represent sins: The Ghost of Hamlet’s Father is not held in chains, and there’s no other metaphorical representation of the King’s sins in his appearance.

So, Dickens could not have drawn solely upon Shakespeare for his construction of Marley’s Ghost. The extensive metaphorical description of the Ghost’s chains and lockboxes as a clear metaphor for his moneylender sins—this is much more reminiscent of the depiction of souls in each Circle of Hell and Terrace of Purgatory.

And, Dante’s idea that sinners are confined to the places of their sin is a key piece of Scrooge’s later epiphany. Here, Marley says that:

“My spirit never walked beyond our counting house–mark me!--in life my spirit never roved beyond the narrow limits of our money-changing hole; and weary journeys lie before me.”

This is where Dickens’ description of the tall City buildings, narrow alleys, and frozen fog fits thematically. The claustrophobia of the City mirrors the lack of empathy of the bankers and moneylenders. If you never leave Cornhill and the shadow of the banks, you do not experience the misery those debts impose on people. Scrooge walked two minutes to his melancholy pub and finished his dinner before Bob Cratchit even got home.

This reflects one of Charles Dickens’ most deeply held beliefs: To really know what’s going on, you have to see it for yourself. Whatever else you can say about Charles Dickens, he got out there. Dickens was a notoriously compulsive walker. He walked the streets of London during the night. He would walk 20 miles at a time. He visited prisons, workhouses, cemeteries–-he was a journalist by nature, and he always went to the source.

So, Marley’s sentence is, apparently, carrying his chains to witness the poverty and misery he spreads. The man who was chained to his desk in life is forced to walk unceasingly in death, to see the world beyond his office. The lesson he has to learn is that:

“Mankind was my business. The common welfare was my business; charity, mercy, forbearance, and benevolence, were, all, my business.”

For Marley, this lack of empathy corrupted his soul, which is why he’s here to visit his partner: Part of his sentence in Purgatory was simply to sit next to Ebenezer and watch him scribble debts in his ledger:

“I have sat invisible beside you, many and many a day…..that is no light part of my penance…to warn you that you have yet a chance and hope of escaping my fate.”

Marley then tells Scrooge that he must endure visits from three spirits, without which, “you cannot hope to shun the path I tread.”

Marley’s ghost walks to the window, and Scrooge looks out: He sees “the air was filled with phantoms, wandering hither and thither in restless haste, moaning as they went.” Scrooge knew them all, these dead souls all wore chains, linked together “like guilty governments.” These specters then fade into the mist, the fog returns, and Scrooge falls asleep, with time-bound appointments with the spirits.

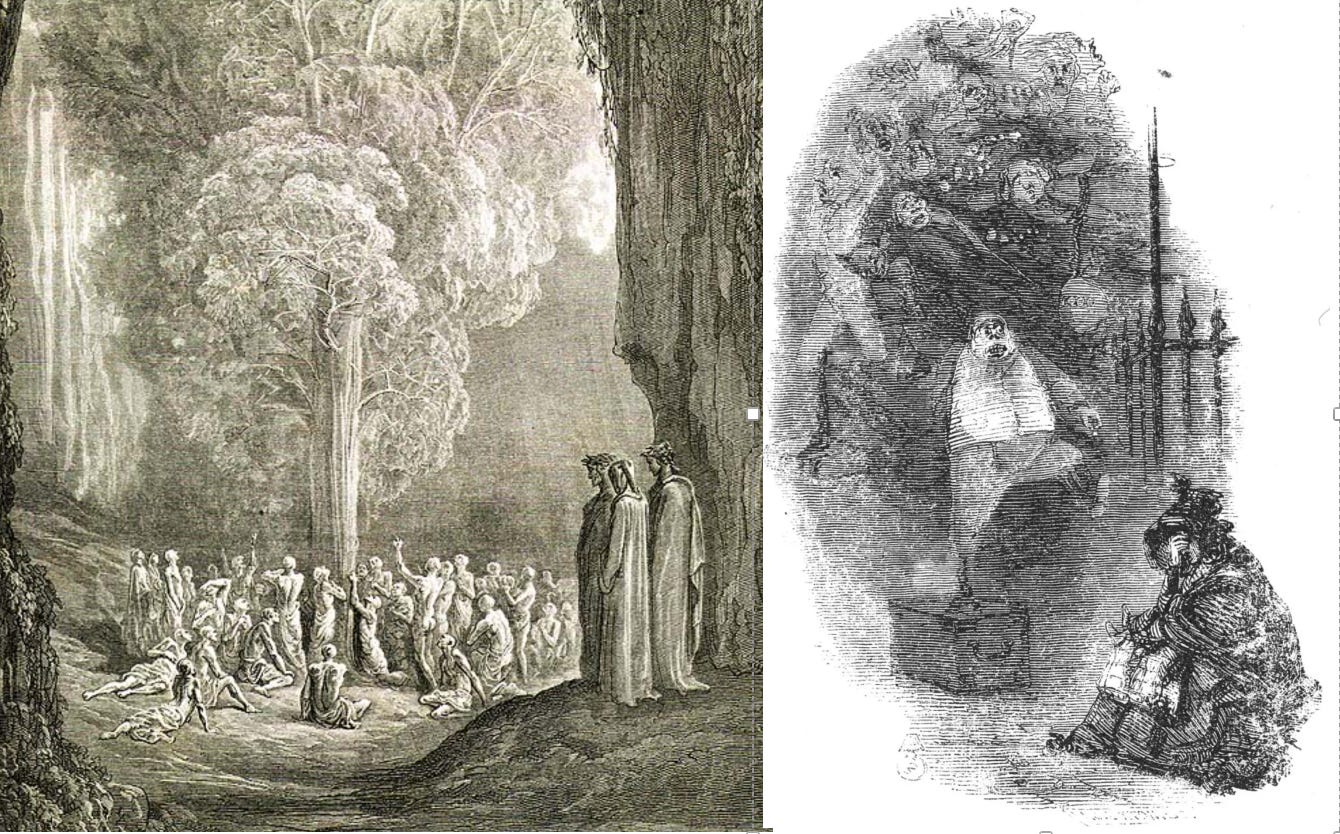

Right: Gustave Dore’s Illustration of Canto 24 of Dante’s Purgatorio, Where Gluttonous Souls Gather Around a Tree of Fruit They Cannot Eat. Left: John Leech’s Illustration of the Trapped Spirits Outside Scrooge’s Window at the End of Stave I.